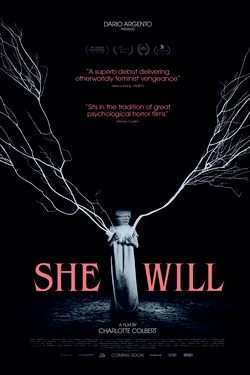

She Will is a creepy art house film from a couple years back. Sometimes cited as a #MeToo film, it was directed and co-written by Charlotte Colbert and it follows an aging child actress recovering from traumatic surgery. Veronica Ghent has decided to go to Scotland, to a remote retreat, to heal. She takes her nurse with her and is chagrined to find that the retreat she booked is being shared by an art therapy retreat. She insists on private accommodations and is put up in an even more remote cabin. While there, it’s made abundantly clear that this was a place where witches were burnt and their ashes mingled with the soil and the very earth therefore has healing properties. Veronica gains an ability to exact revenge from her dreams.

The target for Veronica’s revenge is a famous director who seduced her as a child while working on her first starring role. Famous and powerful, nobody was able to touch him. With her new-found abilities Veronica is able to exact justice through supernatural means. Not only that, but when a local man—the retreat’s handyman—tries to rape her nurse, Veronica is able to prevent that too. This is a moody, sad film that addresses issues that are all too real for many women in a system designed by and intended to profit men. Either unaware of, or uncaring about women’s experiences as participants in the system, they dismiss their trauma in a way they wouldn’t for other men.

Although the film doesn’t have tons of action and doesn’t rely on jump startles, it is an effective gothic horror movie. The Scottish scenery is bleak and evocative and the message is important. Horror films directed by women are starting to gain some notice. Those familiar with Suspiria, however, will note the influence of executive producer Dario Argento. That film also featured the difficulties women can face, and it also concerns witchcraft. She Will is more mature in these areas, however. Female directors—and writers—know the unique struggles women have in a society that refuses to give female leadership a chance. It’s a simplistic world where men are in charge (because the church says so, or, more brutally, because physical strength can be used to get one’s way) and aren’t willing to consider that half the world sees things in a different way. Movies like this force us to take the perspective of another. And for that the world is better.