Unrequited love is sometimes tragic. Other times it’s merely sad. People are attracted to places. Or at least the idea of places. I was born in Pennsylvania, but to a wandering family. I keep looking for roots—my tribe. I didn’t know my father well growing up, but my mother’s family, before taking on that rootless search for greener pastures, was from upstate New York. For several generations. I’ve tried many times to land a teaching post somewhere upstate, but in vain. Even when I knew the people in the department and had been to campus, like that time at Syracuse University. It was raining when I visited, back in my Routledge days. I was taken by what I experienced there, never to be welcomed myself. My family was from a bit further north, around Albany, the head of the Hudson Valley.

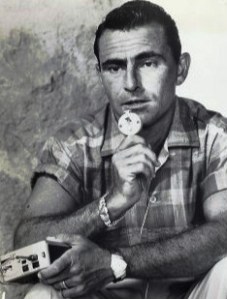

At the time I wasn’t aware that my childhood hero Rod Serling was born in Syracuse. My daughter was at school in Binghamton, which is where Serling grew up. That I knew. Nor did I know that Dan Curtis, creator of Dark Shadows—that other childhood staple—had gone to college at Syracuse. Something about upstate. I’ve remarked to my family that when traveling in this part of the country I catch glimpses of familial facial features in some strangers. A passing glance suggests that they might be distantly related. My unknown tribe. Economics, however, have always kept me away. Even when I explained in my cover letters that I felt that special connection my applications were summarily brushed aside. Probably by folk who knew who their tribe was. Probably from somewhere else.

In this world of internet loneliness, we long for connection. We lived in Wisconsin for over a decade. The only people I really got to know were those I knew from Nashotah House. And this was even with years of involvement with the PTO, serving on the building committee, and even being president one year. People were busy even back then. I was thinking perhaps I’d found my tribe in Wisconsin. But then… The move to New Jersey put me close to my ancestral state, but not in it (my mother was born in Jersey). Economics, that dismal science, dictated that a move had to be back to Pennsylvania, where I was born among strangers. Our nation is one of many tribes, including those we sought to exterminate to steal their land. We have plenty of space, but we value economics over belonging. You may buy the presidency, but you can’t buy your tribe.