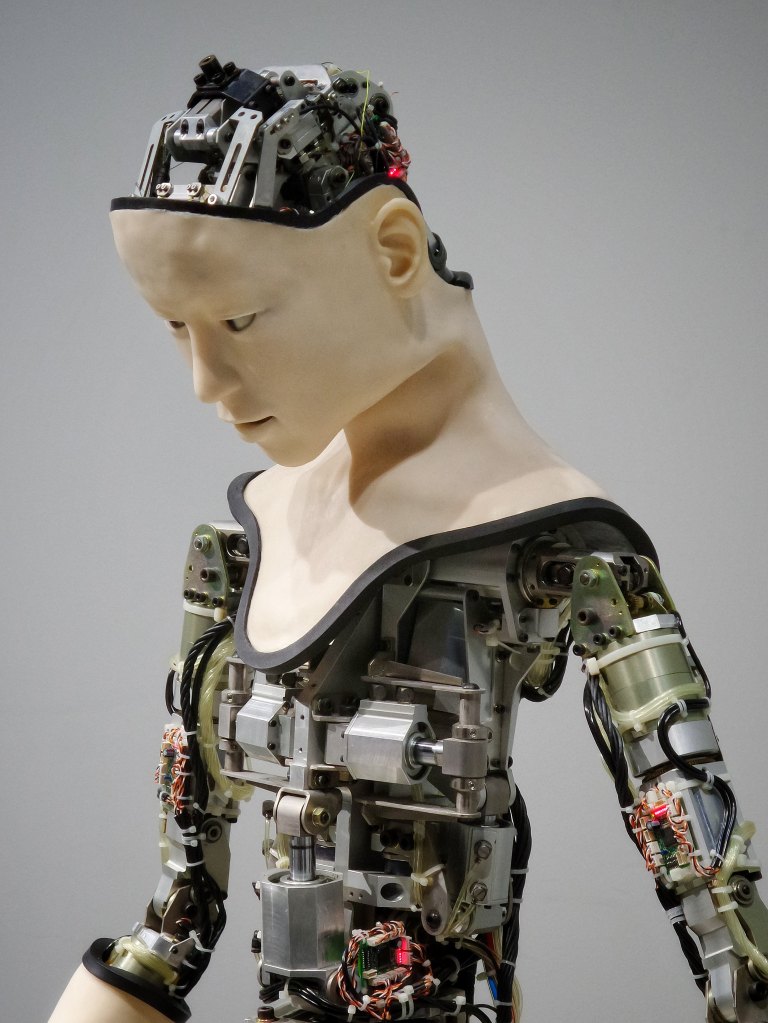

Recently my laptop had to be in the shop a couple of days when a component went bad. This became a period of discovery for me. My laptop is my constant companion. I’m not a big phone user and I have no other devices. Suddenly I had to live without something I’d come to rely upon. It was, in a way, a grieving process. I’ve grown accustomed to being able to check in on the internet when a thought occurs to me. Flip open the laptop and look. Or, if I want to watch a movie, streaming it. Even if it’s a matter of my wife and I wanting to see a “television” series for an evening’s entertainment after work, it has to be done through my laptop. (No other devices will connect to our television, which is, unfortunately, beginning to show signs of requiring replacement.) Just ten years ago this wouldn’t have been such an issue.

Getting the time to take the laptop in required advance planning. This blog, for instance, is dependent on my laptop. I can’t tap things out with my thumbs on my phone—I don’t text—and my phone isn’t that new either. I had to pre-load several blog posts before the laptop went away and figure out how to launch (or “drop,” as the terminology goes) them from my phone. I’m not sure of my neurological diagnosis, but I am a creature of strong habit. That’s how I get books written while working a 9-2-5 job. I’m used to waking up, firing up the laptop, and writing for the first hour or so of each day. I had to figure some other way to do this, without wearing my thumbs down to nubs. This blog is a daily obsession.

And then there was the emotional part. The day I dropped the laptop off—it had to be a weekend because, well, work—I was despondent both before and afterward. Listless, I couldn’t start a new project or even continue work on any because I’d already backed up my hard drive and would risk losing any changes made. (I don’t trust the cloud.) Then I thought, how did I ever survive in the before time? I only became a laptop junkie this millennium, and the majority of my life was in the last one. I recognize the warning signs of addiction. During this period I decided to unplug as much as possible and read more print books. Perhaps that’s the most sane thing I’ve done in quite a long time.