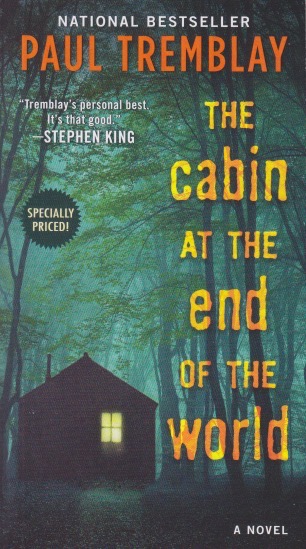

Almost always I come out on the same side of the debate. The book is better than the movie. The book allows things to be explained more fully and is the way the story is “supposed to go.” Maybe it’s because I found the novel open-ended and I like closure, but M. Night Shyamalan’s Knock at the Cabin, in my humble opinion, is better than The Cabin at the End of the World by Paul Tremblay. Now, the author’s title is better, but Shyamalan’s explanation is clearer. In short, I think the movie works better. If you’re not familiar with the story, four apocalypticists, responding to visions they’ve had, break into an isolated cabin occupied by a vacationing family of two daddies and an adopted daughter. Shyamalan characteristically shifts the cabin’s location to Pennsylvania and, yes, before you think it’s all Philadelphia, there are some very isolated places in my home state.

These weaponized apocalypticists subdue the family and inform them that unless they decide which one will be sacrificed, and then carry out the deed, the world will end the next day. The adult couple tries to explain rationally how crazy this all is. How could four people be given this hidden knowledge and be tasked with saving the entire world? It seems more likely that they’ve targeted a gay couple and are trying to break up their family. One of the things the movie makes explicit that the book doesn’t is that the intruders are correct. This is the end of the world. In order to achieve this, Shyamalan had to rewrite the ending to remove the ambiguity. For some of us, that really helps.

The movie, in a way that a brief blog post can’t replicate, includes quite a bit of dialogue about religion. Religion and horror are often bedfellows, and this is one of those movies that relies on religion to fuel the fear. Interestingly, the cabin invaders aren’t stereotypical conservative Christians. In fact, they appear to be mostly secular everyday people who have come together around a vision that they all had in common. In the novel there’s always some question whether this is an elaborate hoax whereas the movie makes it clear that the death of each individual apocalypticist unleashes a plague. Indeed, they are, as the couple finally realizes, the four horsemen of the apocalypse. Since I’m still here to tell you about it, the end of the world has obviously been avoided. This movie is worth seeing, even if the novel has a better title.