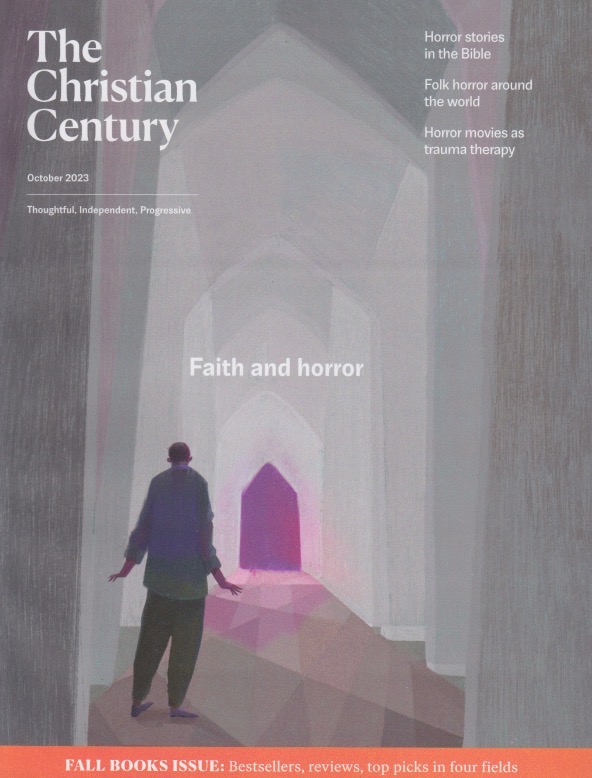

I’m not a magazine reader. When I go to a waiting room (which is quite a bit lately), I tend to take a book. The October issue of The Christian Century, however, caught my eye. As a more mainstream/progressive Christian periodical, CC used to circulate in the office of one of my employers since it features books, the way progressives generally will. This October, however, it featured five articles on “faith and horror.” I had to take a look. I know three of the five authors, one of them without realizing he was a horror fan. An article by Brandon R. Grafius, “The monsters we fear,” discusses the commonalities between fear and religion, ground that he treats in Lurking under the Surface. “The wisdom of folk horror” was written by Philip Jenkins—I didn’t know his horror interest—and it engages, briefly, The Wicker Man. He’s making the point that folk horror is often about somebody else’s religion.

It was “Horror movie mom” by Jessica Mesman that really hit me. Mesman was traumatized in her youth, and like many of us who were, has turned to horror for therapy. This is a moving piece and is worth the cover price of the magazine. Gil Stafford’s “A theology of ghosts” also gave me pause. Stafford is an Episcopal priest who considers ghosts to be more than just woo. In this very personal piece he thinks about what that means. The last feature, “God’s first worst enemy,” is by Esther J. Hamori, one of the colleagues who talks monsters with me. The piece is adapted from her recent book, God’s Monsters. Taken together these pieces are quite a mouthful to chew on. While numbers in mainstream Christianity are declining, Christian Century is still a pretty widespread indication of normalcy.

When I wrote Holy Horror I only knew about the work of Timothy Beal and Douglas Cowan as religion professors writing on monsters and horror. That book admitted me to a club I didn’t know existed—the religion and monster crowd. Since I’m not welcome in the academy, I’m particularly drawn to pieces like Mesman’s since she’s writing from the heart (as is Stafford here). I’m just glad to see this topic getting some mainstream coverage. I know I’m a guppy in this coy pond, but I do hope they’ll consider, over at the Century, turning this into the theme for their October issues in coming years. If they do, they can count on at least one extra counter sale.