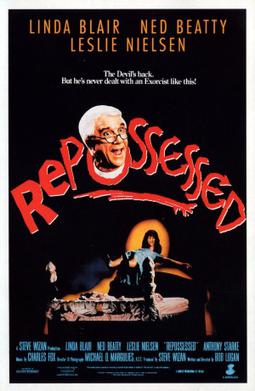

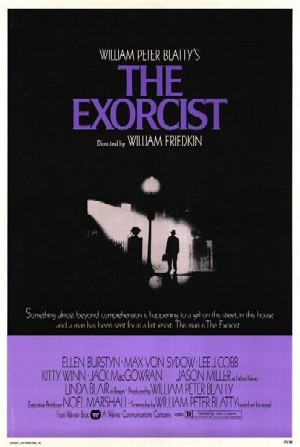

The only reason I heard of Repossessed is because my wife read about it in a local newspaper. This is true although I’d written a book about the Bible in horror movies and a book about possession movies. This one’s been buried deep. Although not a straightforward parody of The Exorcist, it travels the same territory with Linda Blair reprising her role as the possessed girl—now a mom with two adolescent kids. The movie was critically panned, but I have a soft spot for bad movies and it was much better than The Exorcist II. What saves the film is the acting on the part of Blair and of Leslie Nielsen, as the exorcist. Nielsen is pretty funny most of the time, but the gags fall short here time and again. The humor tends toward the sophomoric, but some jokes are good; the Chappaquiddick one was unexpectedly funny. And having a false Donald Trump show up to try an exorcism was an added bonus. These horror tropes classify this as a comedy horror, and it has a kind of cuteness to it that make it worth seeing.

So Nancy Aglet (Blair), after being exorcised by a young Father Mayii (Nielsen), settles down with a family until a televangelist pair—a clear send-up of Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker—actually cause a demon to come through the television. It possesses, or repossesses, Nancy. Since the original movie spends a lot of time in the hospital, she goes to the doctors who can’t figure out what’s wrong. Nancy knows she’s possessed, however, and tries to find a priest to help, Father Mayii having retired. The world’s religious leaders gather as the televangelists fail to cast the demon out on national television, but it’s only when Mayii joins the crew that the Devil is driven out. Not through the rite, but because he can’t stand rock-n-roll, which the religious leaders perform. It’s rather silly, of course.

There is an aesthetic to bad movies and Repossessed is a good example of that. Despite its failings, it’s one of those movies that you’re (mostly) glad to have watched. At least in my experience. Largely, as I say, because of the performances of the leads. Although some people today find The Exorcist itself funny, and although some aspects do open themselves to parody, it takes talent to make fun of it. This film doesn’t do it particularly well. Ironically, Ted Kennedy couldn’t run for president because of Chappaquiddick but Donald Trump, despite having a much more sordid past, could and did. Those two moments in this 1990 movie give me pause. And the fate of the televangelists in it gives me hope.