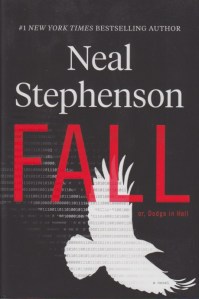

Time. It’s a resource of which I’ve become acutely aware. If I probe this I find that among the assorted reasons is the fact that I’ve finished my fourth book and I realized I’m much further behind that I’d hoped to be at this point. It took me a decade to get Weathering the Psalms published and Holy Horror seems never to have gotten off the ground. I’ve pretty much decided to try to move on to writing that people might actually read, and academic publishing clearly is not the means of reaching actual readers. I can’t help compare myself with prolific writers like Neal Stephenson. (It helps that he’s a relative.) I just finished Fall, Or Dodge in Hell, and was wowed by the impact of both the Bible and mythology on the story. I’ve always admired the way that writers like Neal can not only comprehend technology, but also can project directions into which it seems to go.

Time. It’s a resource of which I’ve become acutely aware. If I probe this I find that among the assorted reasons is the fact that I’ve finished my fourth book and I realized I’m much further behind that I’d hoped to be at this point. It took me a decade to get Weathering the Psalms published and Holy Horror seems never to have gotten off the ground. I’ve pretty much decided to try to move on to writing that people might actually read, and academic publishing clearly is not the means of reaching actual readers. I can’t help compare myself with prolific writers like Neal Stephenson. (It helps that he’s a relative.) I just finished Fall, Or Dodge in Hell, and was wowed by the impact of both the Bible and mythology on the story. I’ve always admired the way that writers like Neal can not only comprehend technology, but also can project directions into which it seems to go.

Not to put lots of spoilers here, but the story of one generation of gods being conquered by another is the stuff of classic mythology. Many assume it was the Greeks who came up with the idea, what with their Titans and Olympians and all. In actual fact, these stories go back to the earliest recorded mythologies in what is now called western Asia. For whatever reason, people have always thought that there was a generation of older gods that had been overcome by a younger generation. Even some of the archaic names shine through here. Like many of Neal’s books, Fall takes some time to read. It’s long, but it also is the kind of story you like to mull over and not rush through. Life, it seems, is just too busy.

There’s a lot of theological nuance in Fall, and the title clearly has resonance with what many in the Christian tradition categorize as the “Fall.” (Yes, there are Adam and Eve characters.) Those who are inclined to take a less Pauline view of things suggest that said “fall” wasn’t really the introduction of sin into the world. Anyone who reads Genesis closely will see that the word “sin” doesn’t occur in this account at all. One might wonder what the point of the story is, then. I would posit that it is similar to the point of reading books like Fall. To gain wisdom. Reading is an opportunity to do just that. And if readers decide to look into matters they will find a lot of homework awaits them. And those who do it will be rewarded.