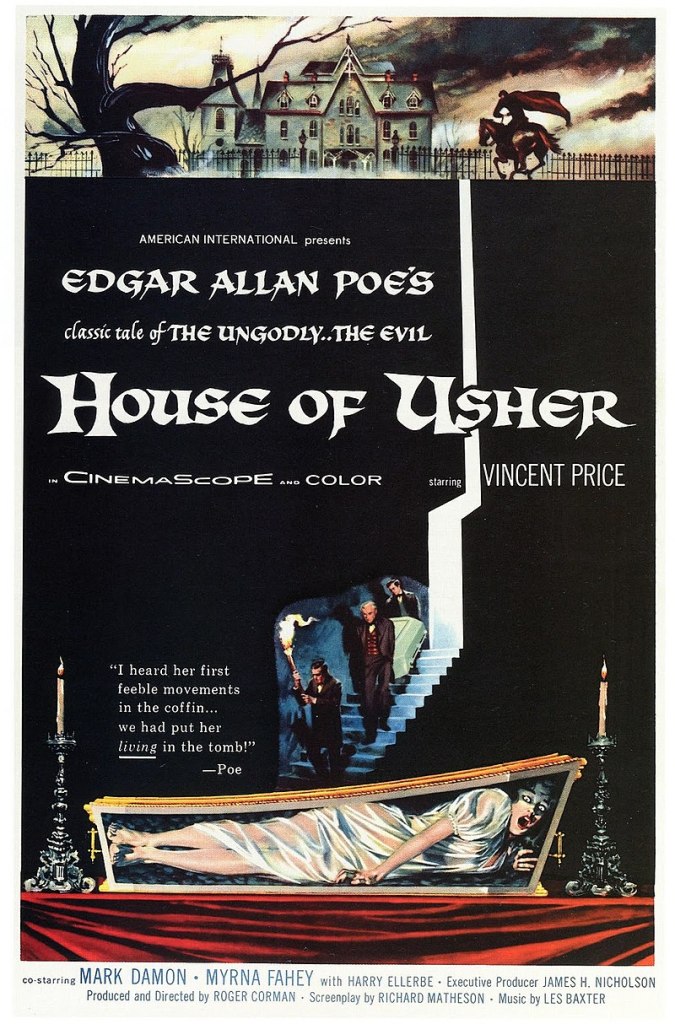

I’m not at all certain I’ll finish it, but at my daughter’s suggestion I watched the first episode of Netflix’s new series, The Fall of the House of Usher. This isn’t set in Poe’s day. The action is in the present and it opens with a funeral for three of Roderick Usher’s children. What’s particularly striking about this funeral is that the priest’s homily is composed of lines from Poe. I think we all know that Poe is undergoing a great surge of popularity these days, but this series seems not content just to name characters and companies after Poe’s names, but it also weaves his thought deeply into the fabric. It uses his images in literal ways that add depth to the plot. I’m not sure that I can spare the time to watch it the whole way through, but I’m sorely tempted to do so.

With C. August Dupin as the Assistant District Attorney, the series ties Poe’s ratiocination stories in with his horror tales. Like most recent media efforts, the cast reflects diversity in many ways. This diversity isn’t the reason the house of Usher is falling, but it’s because of disloyalty. The family owns an unscrupulous company that has shown disregard for the suffering it causes, buying its way out of legal difficulties. (This part is quite realistic and one can’t help but to think of Trump and others like him who simply buy injustice.) But someone in the Usher family has decided to speak out. Dupin won’t reveal who it is, so Roderick and Madeline Usher put the family up to the task of rooting out, and killing, the informant.

Perhaps with some time off over the holidays I’ll be able to catch more of the series. It intrigues me, however, that Poe is being used essentially as scripture. Literally. The priest’s homily fades into the background as the surviving family members check in on each other, but his words are drawn from a variety of Poe’s writings. I’ve long felt that our canon of scripture is too small. Inspired literature did not cease to be written in the second century. As someone who has listened, and still listens to sermons, it’s clear that the Bible alone isn’t a source for knowledge. I haven’t read all of Poe—he left a massive paper trail through his life—but what I’ve read sticks with me and hearing him as sermon material makes me think I need to try to find time in coming weeks to pick up another episode or two.