When I mentioned my book Holy Horror to someone recently, she asked “Have you seen Hereditary?” I had to allow as I hadn’t. I have to struggle to find time to watch movies, and I’m generally a couple of years behind. Surprisingly, Hereditary was available for free on Amazon Prime, and I finally had the chance to terrify myself with it. Perhaps it didn’t help that I’d been reading a book on schizophrenia at the time (as will be explained in due course). Hereditary is one of those movies that is impossibly scary, up until the final moments when it suddenly seems unlikely. In this respect it reminded me of Lovely Molly and Insidious. All three also feature demons. Using a child to accommodate the coming of a demon king brought in Rosemary’s Baby and the Paranormal Activity franchise. (The genre is notoriously intertextual.)

While demons can make movies scary, what really worked in Hereditary was the sense of mental instability and the lack of a reliable character to believe. The Graham family is deeply dysfunctional. Mix in elements of the occult and dream sequences and you’re never certain what, or whom, to believe. As with many of the films I examine in Holy Horror, the realms of religion and fear are interbred. While the Bible plays no part in Hereditary, the matriarch’s “rituals” pervade the family following her death. In a family of females, where a male demon seeks expression through possession, an obviously challenging dynamic is set up. It works out through a series of disturbing images and manipulations.

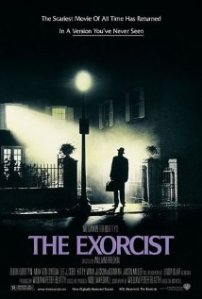

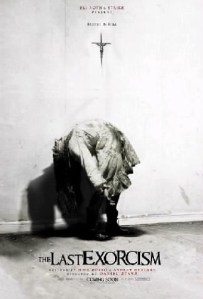

Watching the family disintegrate becomes the basis of the horror. Then possession comes into play. As in most films concerning possession, deception and misdirection are used. A demon named Paimon is seeking to take over the one male heir. This ties the movie to The Last Exorcism, where the same demon under a different name seeks to propagate through Nell Sweetzer. Unlike many possession movies, the suggestion that possession is actually involved comes late in the script. This revelation underscores the the misdirection of attention that focuses on Annie Graham’s struggle to cope with reality. Her sleepwalking and threats to her own children as well as the suggestion that they are but miniatures being manipulated by a larger, more powerful entity, keep the viewer off balance throughout the story. Intelligent and provocative, Hereditary assures me that tying to analyze such films, while perhaps a fool’s errand, is an enterprise unlikely to be soon exhausted.