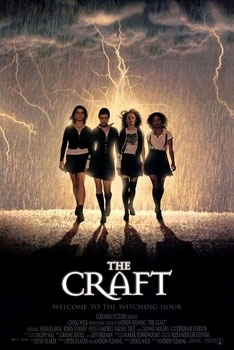

Tis the season for movies about witches. The cult classic The Craft is another one of my old movies—I don’t think I’ve written a blog post about it before. In any case, this autumn felt like good timing for a movie about female empowerment. Rewatching it, it was difficult to miss how religion and horror are tied together. Indeed, the Bible appears in the film as well. This makes sense since the girls attend a Catholic school. So what is this one about? Teenage Sarah has moved to Los Angeles and is having trouble fitting in at school. She is a “natural” witch who catches the attention of the small coven consisting of Nancy, Bonnie, and Rochelle. They invite her to complete their coven so that they can invoke Manon, a deity larger than God. Once they attain their powers, they begin redressing personal wrongs, but begin to hurt others as they do so.

Sarah is the daughter of a witch and her mother died in childbirth. Sarah has difficulties with using powers to hurt others. She was primarily interested in a love spell, but it too has consequences. The coven experiments with even more powerful spells, giving the girls very obvious powers. Especially Nancy. Nancy is angry and enamored of power. Sarah decides she wants out of the coven, but they’ve become too powerful. Since Sarah tried to take her own life before, Nancy tries to force her to do so, only to succeed this time. She’s backed up by Bonnie and Rochelle, both enjoying their powers. Their attack, however, brings out the natural power of Sarah’s witch nature. In the end, all of them lose their powers except Sarah.

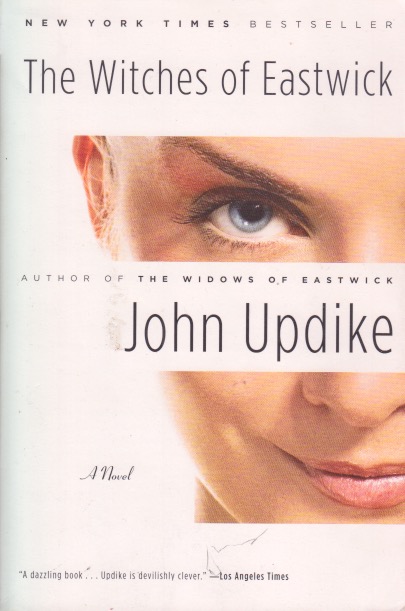

There’s a strong moral streak through the movie. Unrestrained power leads naturally enough to abuses—something we’re living through daily in real life. This is played off against a largely ineffectual Catholic Church. A street preacher, who doesn’t seem very Catholic, also tries to warn Sarah but his method of using snakes is off-putting, to say the least. He dies off pretty early in the film. Religious structures of the monotheistic world have historically closed doors to women. Some still do. The power of nature encompasses both women and men, and the power that women have often frightens men. Again, we see the fear of losing power played out. This is comically addressed in another witch movie, The Witches of Eastwick. Indeed, it is directly addressed there. That’s yet another of my old movies, unless I’ve written about it here before but have lost my powers of memory.