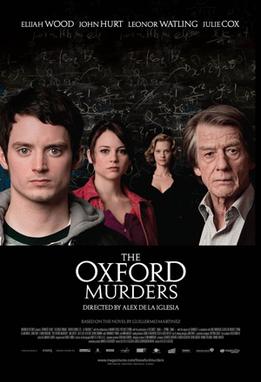

The Oxford Murders isn’t a bad effort as a thriller, but where it works is as dark academia. This 2008 movie didn’t have significant box office take, so it may be one rather unknown. Nevertheless, it is erudite, involving considerable debate about logic (including Wittgenstein) and higher math. So much so that some might get lost. Set in Oxford (and filmed there), it has the dark academia atmosphere down. Since it’s so complex there will be spoilers here, so if you intend to watch it, best do that now.

Here’s a spoiler: the elderly widow of a famed mathematician is murdered by her daughter. The reason for this is that the young woman has fallen in love with an American boarder at their house, but her mother, who has outlived her expectation with cancer—for years—is interfering. Meanwhile, the border (Martin) is obsessed with Arthur Seldom, a brilliant Oxford mathematician. Seldom was in love with the girl’s mother and decides to protect her by making the murder look like the work of a serial killer leaving Pythagorean symbols on the murder notes. Since Seldom isn’t a murderer, he chooses as his “victims” people who’ve already died, making their natural deaths look like murders. This throws suspicion off of the daughter, but when the code and the motivation is published in the newspaper, a man struggling with sanity because his daughter requires an operation, finishes the Pythagorean sequence by killing ten special needs students in a bus crash. Seldom didn’t technically kill anyone, but when Martin confronts him Seldom points out that if he hadn’t boarded with the old woman, her daughter wouldn’t have fallen in love with him and killed her.

The movie is a little clunky, but I think it’s been underrated. There are lots of ideas here that beg to be discussed. Like many murder-mysteries, it has subplots meant to throw you off, one involving a disgruntled mathematician, and another involving a nurse who hooks up with Martin, but who has previously had an affair with Seldom. None of this detracts from the movie as dark academia—something has definitely gone wrong in Oxford. The widow’s murder was a crime of passion, leading to the deaths of innocents, rather like the butterfly effect that the movie discusses. The problem seems to be with the writing. It was based on a novel by Guillermo Martínez, which, I suspect will be added to my reading list. As a movie it’s not great, but it is good for a dark academia fix.