Being busy people, it took us a couple weeks to watch the eight episodes of Tim Burton’s Wednesday, and I think he’s really outdone himself. As I mentioned before, I was never a great fan of The Addam’s Family, but I watched it often enough to know the characters and their quirks. I wasn’t quite sure what to make of the television show. It had monsters, but nothing really scary. It was funny but some of the humor seemed beyond me. I watched it anyway. I didn’t bother with the movie when it came out. Then on a rainy weekend afternoon I watched episode 1 of Wednesday and I was hooked. For one thing, this is dark academia personified. Exclusive, gothic, school, dark mysteries, secret societies. It’s all there. And for another thing, it’s well written and the acting is very good. And then there’s Poe.

(On a side note: I recently found another review of Nightmares with the Bible. It is my most reviewed and least successful book. The reviewer agreed with other reviewers that the Poe angle didn’t convince them. As I told one critic, the Poe angle is a personal one. Poe was a man, a sin of which I’m also guilty. And men of a particular stripe feel protective of women. Maybe it’s one of those biological things we should just get over, but Poe felt that it was poetic and, being a far less intelligent experiencer of that same disposition, I feel it too. I think Tim Burton might also, for Wednesday seems full of that as well.)

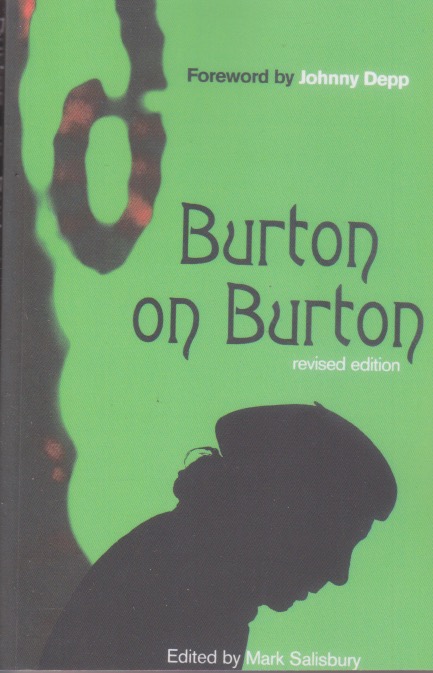

At Nevermore Academy, the morbid, anti-social loner Wednesday learns to accept a kind of friendship from other outcasts. There’s a town vs. gown aspect as the residents of Jericho don’t exactly love the academy, but they appreciate the money it brings in. The founding pilgrim, Joseph Crackstone, was a hater of those who were different and tried to rid the world of others not like him (this is important). Over eight episodes this backstory interrupts into the present and threatens the very existence of Nevermore. What ties it all together, of course, is Wednesday. Nearly as gothic as Sleepy Hollow, this Netflix series showcases the aspects of Burton’s vision that I find most compelling. And the first season was nominated for quite a few awards. A second season has been approved and I’ll be watching that one, down the road. I can’t get enough dark academia these days, no matter the day of the week.