Few experiences encapsulate one’s lack of control like commuting by bus. As my first year of a daily commute to Manhattan draws to a close, I have experienced many mornings of standing in cold or hot air while a bus leisurely makes its way toward my appointed stop twenty, thirty minutes late. The commuter can’t head back home for a moment’s warmth/coolness, because the bus could come at any time. The sense of utter helplessness as you know that you’ll be late for work, and that you got up at 3:30 a.m. for this, settles like an iron blanket over what might have begun as an optimistic day. Then there are those who sit beside you, totally beyond your control. I’m a small guy and I sit scrunched next to the window to get as much light for my reading as I can. Very large people find the extra space next to me attractive, although sometimes they insist I squish even more against the window so they might fit. Overall, however, the exchange of comfort for reading time makes the arrangement palatable. It’s the loss of time that bothers me.

Without traffic, my bus can be at the Port Authority Bus Terminal in an hour. To manage this feat, it has to reach my stop before 6 a.m. On rare occasions it comes perhaps five minutes early. When you take a bus, subject to the vagaries of traffic, the only wise course of action is plan on being a few minutes early. Drivers who watch the clock are dangerous. So it always annoys me when passengers down the line complain if a bus is one minute early. On those exceptional mornings I hear strident voices raised, “you’re two minutes early—I had to run!” or “I was sitting in my car; you came too early!” The driver is scolded and the next day we’re all half an hour late for work. It is the problem of premature transportation. Time, to the best of our knowledge, is something you never get back. I would rather be early rather than late.

I first conceived of wasted time as a religious problem when I was in seminary. There was always so much to do, and relinquishing time to pointless activities such as standing in line, or waiting for the subway, grew acute. Now that I’m an adult anxious about holding down a job that requires a lengthy commute, the issue has arisen again. Clearly part of the difficulty lies in that time is frequently taken from us. The nine-to-five feels like shackles to a former academic. I had classes anywhere from 8 a.m. to 10:30 p.m. without considering the drain on my time. It was largely, I believe, because pointless waiting was not very often involved. Time, like any limited resource, must be parceled out wisely. Time to bring my morning meditation to an end and get ready for the bus. And if it’s early I will consider it as a divine gift.

Used Against You

Many times I’ve confessed to being a reluctant Luddite. My reluctance arises from a deep ambivalence about technology—not that I don’t like it, but rather that I’m afraid of its all-encompassing nature. This week’s Time magazine ran a story on how smartphones are changing the world. My job, meeting the goals set for me, would be impossible without the instant communication offered by the Internet. Everything is so much faster. Except my processing speed. We all know the joke (which would be funny if it weren’t so true) that if you’re having trouble with technology, ask a child. In my travels I see kids barely old enough to walk toddling around with iPhones, clumsily bumping into things (i.e., human beings) as they stare at the electronic world in the palm of their tiny hands. And once the technocrats have taken over, “progress” is non-negotiable.

I made it through my Master’s degree without ever seriously using a computer. Even now I think of this very expensive lap-warmer before me as a glorified word processor. Over the weekend I succumbed to the constant lure of Mac’s new OS, Mountain Lion. Some features of this blog had stopped working, and, being a Luddite, I assumed that it was outdated software. Of course, to update software, you need an operating system that can handle it. So here I am riding on a mountain lion’s back, forgetting to duck as the beast leaps dramatically into its lair. In this dark cave, nursing my aching head, I realize that I have become a slave to technology. For a student of religion who grew up without computers, I’ve got at least half-a-dozen obsolete ones in my apartment, each with bits and fragments I’m afraid to lose, despite the fact that I’m not even sure where to take them to retrieve the data. When I sat down to write my post this morning I received a message that Microsoft Word is no longer supported by Mountain Lion. Fortunately my daughter had the foresight to purchase Pages, so life goes on.

This blog has an index. It is an archaism. Indexes are not necessary with complete searchability. It is there mostly for me. In my feeble attempts at cleverness, I sometimes forget what a post is about, based on its title. The index helps me. In a truly Stephen King moment, I found this morning that my index had infinitely replicated a link to my post on the movie Carrie, so that any link after that will lead you directly to the protagonist of Stephen King’s first novel. It will take a few days to clean that up. There’s probably an app for it. For those of us brought up before household computers were a reality, however, there is a more religious explanation. Yes, my laptop is clearly haunted. And in the spirit of Stephen King I type these words while awaiting the top to snap down with the force of an alligator byte and break off my fingers. I should be worried about it, but instead, I’m sure there’s an app to take the place of missing digits. Even if there isn’t I’m sure my iPhone will happily survive without the constant interference of a Luddite just trying to call home.

Danger de Nuit

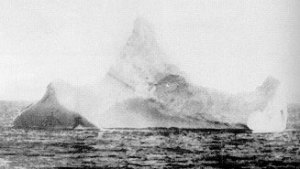

I am on a boat—maybe it’s the Titanic. Far from land. For some reason, vaguely unclear, the ship is sinking. There’s panic—people are running and flailing, trying to save themselves. I’m frozen with terror as the icy water encroaches. I can’t swim. I prepare to die. So goes a nightmare I had several times in association with a former place of employment. Nashotah House felt traumatic to me with forced liturgies and daily reminders of my inferior status. The terror of the nightmares was very real, and the day I was fired did nothing to improve them. As a child I was plagued with phobias and frequently experienced horrific nightmares. They still come once in a while, but since I’ve left the employment of the church, they have become, gradually, less frequent. Nightmares are just dreams gone bad, and I’ve always been a dreamer.

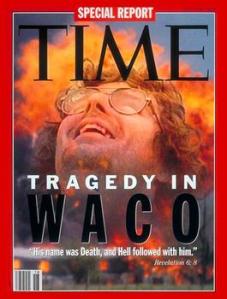

Last month Time ran a story on nightmares. The subject of nightmares has now caught the attention of the military because of cases of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. When the military decides to show its humane side, it doesn’t fear backing it with big bucks. Soldiers confess to frequent nightmares after witnessing the atrocities of war. (One psychologist said that many at Nashotah House seemed to be suffering from a similar phenomenon.) Theorists now suggest that nightmares might lead to mental illness, and sleep deprivation, as we all know, can lead to bad judgment. Not a good thing on the battlefield. Or behind the wheel of a car. Or, in a recent real-life nightmare, while flying a jet.

In many ways nightmares seem like minor annoyances—they don’t physically hurt anyone, and they end when you wake. Time probably wouldn’t have reported on them if it hadn’t been for the military angle. This seems a paradigmatic situation. A common problem goes ignored until it affects the military, then it is deemed worth research funded by tax-payers. I am well acquainted with nightmares. As a child they became part of my identity. I am heartened that serious research is considered worthy of federal money. It seems, however, that perhaps a better way to end battle-induced nightmares would be to stop the horrors of warfare. When war ends, some nightmares will cease. Of course, I’ve always been a dreamer.

Final Flight

Back in the day before CD players, let alone MP3 files, my mom had a squat, boxy rectangle of a cassette-tape player. (Remember, I am a student of ancient history.) The cassettes we had were home recorded, scratching and hissing like a disgruntled cat, but they were the latest in technology. And, of course, they were religious in nature. One particular tape I still remember with terror. Narrated by a optimistically doleful bass male voice, it recorded the events surrounding those climbing aboard a plane bound for heaven, along with authentic jet noises. It was, of course, a thinly disguised metaphor for death, something I realized even as a child. As the passengers climbed aboard, anticipating that meeting with Jesus, I trembled in fear. They were all about to die.

I have never been particularly afraid of death. Not that I’m in a hurry to go there, but I have always sensed it as inevitable and therefore not worth worrying over excessively. I was one of those who grew up thinking quite a lot about it, viewing it from different angles, trying to make sense of it. I still do. While I was in England, Time magazine ran a cover story on Heaven. Now that my feet are back on the ground, I have been reading the story with interest since I’ve just been spending several hours on a jet in the sky. One of the most surprising elements in the story is the fact that some evangelical preachers are beginning to inform their flocks that heaven is what we make it here on earth.

I have never been particularly afraid of death. Not that I’m in a hurry to go there, but I have always sensed it as inevitable and therefore not worth worrying over excessively. I was one of those who grew up thinking quite a lot about it, viewing it from different angles, trying to make sense of it. I still do. While I was in England, Time magazine ran a cover story on Heaven. Now that my feet are back on the ground, I have been reading the story with interest since I’ve just been spending several hours on a jet in the sky. One of the most surprising elements in the story is the fact that some evangelical preachers are beginning to inform their flocks that heaven is what we make it here on earth.

This may not sound shocking to you, but having grown up evangelical I knew that the only reason we behaved so well all the time was so that we could get into Heaven when we died. This was the economic basis of salvation—you paid for Heaven in good deeds and correct belief. Not that you exactly earned it, but you did invest in it. This was the defining characteristic of Christianity. The suffering that is so obvious in the world (I saw three homeless men curled up together inside the Port Authority Bus Terminal just this morning) can harsh anyone’s paradise. The traditional “Christian” response has been to look past that to a shimmering, if imaginary, kingdom in the clouds. I am very surprised that some evangelical pastors are willing to risk their entire campaigning platform in order to help those in need. It’s getting so that it is hard to tell which way is up any more. Maybe that’s what happens when you spend too long on a plane bound for a mythical destination.

Too Tired or Not too Tired?

An article in the current Discover magazine ponders invisibility. Sight is actually the perception of certain wavelengths of light, and by bending particular wavelengths around an object it can be rendered invisible. There’s nothing really new there, as anyone who’s heard of the Philadelphia Experiment knows. The next step of the quest, however, is to determine if, by sending parallel light rays at manipulated speeds, an event might be rendered invisible. Event in this sense of the word currently denotes an event on a cyclotronic scale, an incredibly miniscule and inconceivably brief occurrence. Since humans are endlessly inventive, the corollary is naturally what might transpire from there as larger events are targeted and rendered clandestine. Could an historic event be lived out in (or engineered into) complete obscurity? It sounds like science fiction, but these questions are being asked in the workaday world in which we live.

An article in the current Discover magazine ponders invisibility. Sight is actually the perception of certain wavelengths of light, and by bending particular wavelengths around an object it can be rendered invisible. There’s nothing really new there, as anyone who’s heard of the Philadelphia Experiment knows. The next step of the quest, however, is to determine if, by sending parallel light rays at manipulated speeds, an event might be rendered invisible. Event in this sense of the word currently denotes an event on a cyclotronic scale, an incredibly miniscule and inconceivably brief occurrence. Since humans are endlessly inventive, the corollary is naturally what might transpire from there as larger events are targeted and rendered clandestine. Could an historic event be lived out in (or engineered into) complete obscurity? It sounds like science fiction, but these questions are being asked in the workaday world in which we live.

Messing with history is related to fooling about with time. Twice every year we attempt to manipulate the standard determined by our sun and human convention to set clocks forward or back to maximize daylight at certain hours. We are rendering times invisible. Every year when I groggily adjust to the new time scale, I grumble about how wasteful it really is. Being one of those people who wakes up before the alarm clock goes off (I had never even heard the alarm on my current clock), twice this week I have found myself startled awake by the foreign beeping next to my head. In disbelief I stare at the 4 a.m. displayed in placid blue digits floating in the dark. Well, changing three time zones the day before setting clocks ahead probably didn’t help, but I wonder why we don’t just leave time alone.

Waiting for the bus in the dark, a silent kind of joy begins to grow as daylight creeps into those murky morning hours. Then we fool about with time and plunge those on the verge of daylight back into the darkness. Just that one hour leaves a nation yawning uncontrollably for a couple of weeks until our bodies adjust to the new schedule. Why can’t we leave time alone? People are never satisfied with time as it is, but since we can’t seem to stop it, perhaps we can render select portions of it invisible. The potential for abuse seems awfully large to me. Let’s put it to a vote. If we are going to make one historical event disappear, I suggest we do it twice annually. And those events would be the insane toying with time by setting our clocks ahead and back. Excuse me, but I feel another yawn coming on.

Theomockracy

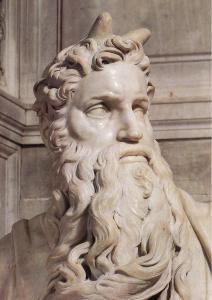

“From Santorum to Graham, the ferociously religious are doing religion no favors at the moment, and it’s beginning to feel as though we may need to save faith from the extreme pronouncements of the faithful,” so writes Jon Meacham in this week’s issue of Time. Theocracy is a scary word. It didn’t work in ancient Israel, and it is difficult to believe that our society is morally more advanced than things were back then. I mean, they had Moses looking over their shoulders, and Amos, Isaiah, Micah, and Jeremiah to point out each misstep. We have Santorum, Bachmann, Palin, and Gingrich. This playing field would be an abattoir, and I have no doubts that the true prophets would be the only ones left standing should it come to blows. The odd thing is, the ancient Israelites, evolving into the Jewish faith, came to recognize that maybe they misunderstood some of what their stellar, if mythic, founders were saying. Rule by God is great in theory, but in practice it leaves a nation hungry.

It is difficult to assess the sincerity of modern day theocrats. We know that politicians are seldom literate or coherent enough to write their own speeches, and we know that they tell their would-be constituents what they want to hear. It shouldn’t surprise us that they belch forth juvenile pietism and call it God’s will, for we have taught them that elections are won that way. My real fear is that one of them might mean what they say. Could our nation actually survive even half a term with a true theocrat at the helm? W may have played that role, but there was a Cheney pulling the strings behind the curtain. Some guys like the God-talk, others prefer to shoot their friends in the faces. Either way it’s politics.

I take Meacham’s point. In all this posturing and pretending, the would-be theocrats are making a mockery of what the honestly religious take very seriously. If they want to get right with God there are conventional channels to do so. The White House is not one of them. They swear to uphold the ideals of the Constitution that, with considerable foresight, protects us from theocracy. The history they prefer, however, is revisionist and their constitution begins with “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” Their use of the Bible offends those who take the document seriously. Theocracies have never worked in the entire history of the world. Those who ascribe to mythology as the basis for sound government should add Thor, Quetalcoatl, and Baal to their cabinet and pray for a miracle.

Scared Mittless

Once again Time magazine has presented an article where the intelligent are left scratching their heads about religion. Jon Meacham’s Commentary, “An Unholy War,” details how evangelical concerns about Mitt Romney’s Mormonism has an undue weight in regard to his presidential candidacy. For many years the media industry has considered religion passé and without teeth. Sure, the street-corner preacher can still give you a good gumming, but it is rarely fatal. What those who’ve never felt the utter urgency of religion can’t appreciate is, well, its utter urgency. In a day when Buddhist monks and Catholic nuns are wired up to electrodes and told to find that spiritual sweet spot, it is easy to forget that these aren’t just laboratory fictions. For many people in the world, their religious experiences are very important and of sometimes deadly—sometimes eternal—consequence. The sophisticated, the educated, laugh it off as so much hoodoo, and try to get on with human progress. For those raised religious, however, escape is neither easy nor desirable. Those in positions of actually influencing the public need to recognize that religion is not a luxury, a trapping that might be cast off. It is a life choice cast in iron.

Just as serious as the analysis of religion is the incredible influence of religious teaching itself. Take a young child, barely old enough to understand death, and tell him or her that the worst thing they can imagine just can’t compare with the torment God has cooked up for those who step out of line. Repeat. At least once a week. When said child becomes an adult, these early ideas are deeply embedded. Since the 1980s elections in the United States have been restyled as religion popularity contests. With eternal consequences riding on the ballot, political analysts ought to be required to have had taken at least Religion 101. Probably a few upper-level courses would also help. Despite the optimism of scientists and academics, religion is not going away. The reluctance to take it seriously will not diminish its power in people’s lives.

As became very clear reading Philip Jenkins’ Mystics and Messiahs, it has only transpired that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day saints has been recognized as un-culted for less than a hundred years. As a relatively new religion, Mormonism was a “cult” until it had survived long enough to gather a band of respectable followers, such as Mitt Romney. Many Christian groups, particularly evangelical ones, have not released their perception of Mormonism as a cult. Romney, in their eyes, is effectively as pagan as Obama. Their votes, as the eight-year nightmare of the Bush administration demonstrates, can decide elections. Still, we the sophisticated laugh off the country rubes who still believe in God. And although we don’t believe in it, we already have, and may well once again, come to suffer through Hell to show just how educated we are.

Yeti Again

Time magazine announced last week, in a story spelled out on Time.com, that “There may be solid evidence that the apelike yeti roams the Siberian tundra.” This is surprising news given that even in the face of good evidence, science is reluctant to admit new large animals to our biological family. The reasoning goes that since humans (mostly white, male humans of the western hemisphere) have explored most of the landmass on this planet, we could not have missed any large land creatures. There are rare exceptions, such as the mountain gorilla, added to our database only about a century ago, but it seems to have been the last of the large animals to avoid detection. Now the yeti, the bogeyman of many childhood dreams, may be coming to life.

Science is our way of describing and theorizing about what we have discovered. Many therefore assume that science is all about new discoveries. Some of us feel a tinge of sadness at having been born after the great era of discovery. Reading about how adventurers (responsible for far more fundamentally earth-shaking discoveries than scientists of their times) ventured into new worlds and declared the wonders of God revealed in the formerly unknown, is always a humbling experience. We know so little. The mark of the truly educated is not the claims of great knowledge, but the admission of how little we really understand. Does the yeti roam the inhospitable and very sparsely populated regions of Siberia and the Himalayas where it has been a staple of folklore for centuries? We may never find definitive proof, but Time holding out a candle of hope seems a step in the right direction.

Relegated to the world of the “paranormal,” elusive animals demonstrate that the ways we know about the world are multitude. Science does not, and does not claim to, know everything. Indeed, science has a limited frame of reference within which it works. Going out seeking cryptids is not, properly speaking, science. The belief that those seeking evidence display is closer to religious conviction. That does not mean it is wrong or that it is founded upon faulty suppositions. It is simply a different kind of knowledge. It is common to say science is in conflict with religion. It need not be. If we accept science at its word, as doing what it claims to do, there is no need ever to question assured results. Belief, on the other hand, seldom crosses over into the realm of objective truth, empirically demonstrated. If it did, it would not require believing. If yeti is discovered, there will be much celebration among believers, but the creature will necessarily pass into the hands of science. For this reason alone, many are glad to leave it in the realm of folklore and myth. Either way, to some people, yeti will always be real, whether scientifically verified or not.

Timing God

Two weeks in a row now God has made it into the pages of Time magazine. You’d think he was Rick Perry or something (no insult to God intended). This week’s Commentary, written by Harvard physicist Lisa Randall, argues for the importance of believing what science forces us to conclude. The world is warming up, ice caps are melting, and those in low-lying regions are in hot water. I am fully in agreement with her sentiments, but it’s the practicality that bothers me. Not the practicality of listening to science—that’s just common sense—but the practicality of doing so in a world where religion reigns. Despite cries of oppression and suppression and repression—just about any pression you choose—religions dominate the world. What particular brand you prefer does not matter; the fact is most people are religious. Randall believes that religion and science must learn to live together. Her problem is that she is looking at it rationally.

Science has given us excellent leads on tracing the origins of religion itself. Between psychology, anthropology, sociology, and biology we’ve got a fair idea how religion came about. The same brain that shows us the way, however, has evolved with religion still intact. In short, it has learned to accept the unlearned. With our brains acting like dogs chasing their own tails, is it any wonder that as a species we are confused? We see only what we choose to. In the great, artificial landscape of Manhattan many very wealthy people traverse the streets. Every day I see suits that would cost my entire paycheck casually strolling up Madison Avenue. I also see the beggars in the same doorways day after day, blending in with their surroundings. The solution of choice is to pretend they aren’t there, to not accept the evidence of our eyes. The wealthy have a knack for it, it seems. And when they work their way into politics their vision doesn’t improve much.

The problem that Randall points out is very real and deadly serious. Trouble is, those who pretend not to see are among the best actors on the planet. Faced with incontrovertible evidence the rational mind has no choice but to acquiesce. Religion, however, offers the perfect escape clause. If global warming discomforts you too much try fanning yourself with a Bible. Soon the excess degrees will simply melt away. And when the religious enemies of science find themselves sitting on the ocean floor like the victims of the Titanic, they too will have the satisfaction of knowing that they were privileged above all people for the time they had on earth. Everyone wins. The insatiably greedy and the abjectly poor both share a spot on an overheated planet. And if the pattern holds true we’ll evolve eyes to read under water, along with our gills, so that we can continue to read our waterlogged Bibles to find out what’s coming next.

Lead us not into Dominion

Christian dominionists emulate the Roman Empire, it seems. The Viewpoint in last week’s Time magazine, entitled “In God We Trust,” points out several of the objectives of the dominionist camp. Taking their cue from a decidedly modern and western understanding of Genesis 1, this sect believes the human control over nature to be a divine mandate in which our species dominates the world, with divine approval. As Jon Meacham points out, that dominion does not end at other animal species, but includes control of the “non-Christian” as defined by their own standard. This non-negotiable “Christianity” is a religion guided by utter selfishness and self-absorption. So thorough is this directive that those indoctrinated in it cannot recognize Christians that do not share its perspective as part of the same dogmatic species. It is a frightening religious perspective for a nation founded on the principle of religious freedom.

Rehearsing the rhetoric from Rick Perry’s “the Response” rally, Meacham rightly points out that when dominionists quote the Bible it is most important to note what the Bible does not say. Herein lies the very soul of the movement—filling in the void where God does not talk with human desires and ambitions. As any good marketer knows, however, packaging can sell the product. Introduce a rhetoric that claims to be biblical to a nation where most people have never read the Bible and smell the recipe for success. People want to believe, even if what they think they believe is not what it claims to be. Christianity is claimed by so many vastly differing factions as to have been drained of its meaning. This is the danger in the game of injecting religion into politics. Surely the Perrys and Palins and Bachmanns know what they believe, but they do not say it aloud, for their Christianity does not coincide with the various forms of the religion advocated by the churches historically bearing the torch of Christ’s teachings, insofar as they might be determined.

Dominionism is nothing new. Even the most pristine believer must see that Constantine had more than a warm fuzzy feeling in his heart when he adopted a foreign religion and fed it to his empire. No, Christianity was an effective, non-violent means of control as well as a way of achieving life after death. Rome was nothing without dominion. The parallels with the United States have been noted by analysts time and again. As we watch the posturing of political candidates wearing some form of their faith on their sleeves, the unsuspecting never question what might be up those sleeves. It is fairly certain that when the parties sit down at the table and the cards are dealt, it won’t be Bibles that we find scattered there. This is not a kingdom of God’s making. When dominionists take over all others must scan the horizon for the advent of the Visigoths who will not be dominated.

Dominionism is nothing new. Even the most pristine believer must see that Constantine had more than a warm fuzzy feeling in his heart when he adopted a foreign religion and fed it to his empire. No, Christianity was an effective, non-violent means of control as well as a way of achieving life after death. Rome was nothing without dominion. The parallels with the United States have been noted by analysts time and again. As we watch the posturing of political candidates wearing some form of their faith on their sleeves, the unsuspecting never question what might be up those sleeves. It is fairly certain that when the parties sit down at the table and the cards are dealt, it won’t be Bibles that we find scattered there. This is not a kingdom of God’s making. When dominionists take over all others must scan the horizon for the advent of the Visigoths who will not be dominated.

Bell’s Hell

Hell makes the cover of Time. Or at least its absence does. For those of us who’ve delved deeply into the Bible for many years, it is no surprise. In fact, the uproar, as Time confesses, is among Evangelicals. So why Hell? Why now? The Evangelical pastor of Mars Hill Bible Church, Rob Bell, has just published a book questioning the existence of Hell and his fellow Evangelicals are in a conflagration about the loss of the sacred icon of God’s omnipotent stick that threatens them all into Heaven. It is a sad day when love cannot encourage enough that hatred becomes religion’s motivating factor.

The loss of Hell, however, represents so much more than just the loss of the scariest place under the earth. It represents the loss of control. Without Hell to wield and Hell to pay, many of the faithful may wonder what they might get away with. Neo-cons have been eager to court the Hell-mongers because the issue is making others lock-step in their own pattern. Diversity is not encouraged or appreciated. Lawns must be cut to the same height, trees carefully trimmed, shirts must be conservative and cookie-cutter, and one must wear that blessed smile that proclaims “Hell-dodger.” Cast any doubt into this fabled world and the results might be, well, realistic.

The Hebrew Bible knows no Hell but the one we make for ourselves. We hardly need a Devil to tutor us in the ways of evil. Human history reveals that we’ve had it in us all along. Instead of celebrating the death of Hell, several Evangelical pastors are simply adding Bell to its numbers. Time’s news is not news for many of us, but for those who haven’t considered seriously the implications of their faith as Holy Week rolls around, this may be a good time to take stock of options for eternity. What do we gain by fabricating an eternal torment devised by the most loving deity ever conceived? Hell can now claim its rightful place as a metaphor for the wickedness Homo sapiens devise for each other and for their planet.

Time Isn’t Holding Us

Ancient is much more recent than it used to be. Perhaps it has something to do with the two massive earthquakes over the last couple of years that have together sped the earth’s rotation by almost three microseconds. Perhaps. A more likely explanation is that excessive technology makes us soft. We expect new toys, new tech solutions on nearly a daily basis, and with the communications revolution, we are rarely disappointed. I wonder if we’ve forgotten how to help ourselves. This is especially evident in the lack of initiative I sense among many students. Of course, I am ancient.

When exam time rolls around, the present-day student requires a study guide. When I was a student, after dodging all the dinosaurs running around the campus, I never received a study guide for a test. If a test is coming, read, re-read, i.e., study, your notes. Maybe read a textbook? Nowadays a study guide is required for that message to be sent home. And then there’s the emails. Once the study guide is distributed (electronically, of course) the emails gush in asking what exactly I mean by this or that. Since I reiterated the point endlessly in class, accompanied by a PowerPoint slide with the answer writ large, verily, I roll my eyes and drop to my three-legged stool in dismay. Can it really be that college students require detailed answers in advance for a multiple-choice test of only 40 questions? Back in my day, a multiple-choice test was a gift that felt like sixth grade had rolled around again.

Time, since Einstein, has been relative. And since I am an antiquity, I can perhaps be forgiven for citing Supertramp’s “The Logical Song.” As a studious young man, religious from epidermis to viscera, I was sent off to get an education. Years later, kicked out of the academy for good behavior, I see the wisdom of the lackluster 70’s band: “But at night, when all the world’s asleep, the questions run so deep for such a simple man.” The lyrics are easily found on the Internet. It is simpler than walking over to the CD rack to check manually. Back in my day, I would never have even imagined skipping an exam and then asking the professor what he was going to do about it in the next class period. Email, in this instance, is easily forgotten. I’ll get back to you once I engage the electronic lock to keep out this velociraptor (if anyone can remember back to 1993).

When Machines Fall in Love

When I want to have a good scare, I seldom think to turn to Time magazine. This week’s issue, however, has me more jittery than a Stephen King novel. One of the purest delights in life is being introduced to new concepts. Those of us hopelessly addicted to education know the narcotic draw of expanding worldviews. Once in a while, however, a development changes everything and leaves you wondering what you were doing before you started reading. A change so profound that nothing will ever return to normal. Singularity. The point of no return. According to the cover story by Lev Grossman, we are fast approaching what theorist and technologist Raymond Kurzweil projects as the moment when humanity will be superseded by its own technology. The Singularity. Noting the exponential growth of technology, Singularitarians – almost religious in their zeal – predict that computing power will match and then surpass human brain speed and capacity by 2023. By 2045 computers will outdistance the thought capacity of every human brain on the planet (more challenging for some than for others, no doubt). The software (us) will have become obsolete.

A corollary to this technological paradise is that by advancing medical techniques (for those who can afford them) and synching tissue with silicone chip, we may be able to make humans immortal. We will have finally crossed that line into godhood. Kurzweil notes laconically, death is why we have religion. Once death is conquered, some of us will be left without a job. (Those of my colleagues who actually have jobs, that is.) We have empirically explained events as far back as the Big Bang, and no deities need apply. The evolution of life seems natural and inevitable with no divine spark. And now we are to slough off mortality itself. O brave new world!

There was a time when mythographers created the very gods. They gave us direction and focus beyond scraping an existence from unyielding soil. We have, however, grown up. There are a few problems, nevertheless. Scientists are no nearer explaining or understanding emotion than they were at the birth of psychology. We might explain what chemicals produce which response, but we can’t explain how it feels. Emotion, as the very word indicates, drives us. Until Apple comes out with iMotion and our electronic devices feel for us we are stuck falling in love for ourselves. Computers can only do, we are told, what they are programmed to do. The mythographer steps down, the programmer steps up as the new God designer. Having dealt extensively with both, I feel I know which I trust better to provide an emotionally satisfying future.

10 Questions

This week’s Time magazine’s 10 Questions feature is directed to Stephen Hawking. Predictably, the first one concerns God. “If God doesn’t exist, why did the concept of his existence become almost universal?” a reader asks. I was less concerned with the answer than with the implications of the question itself. The very question represents a paradigm shift. Time was, such questions were directed to local clergy. The minister had the answers. To be sure, many millions, if not billions, of people regularly rely on their clergy for divine guidance. I used to teach clergy, so I am wary. Today, however, we need to know if all the answers fit. To find out if God exists, ask a scientist.

This week’s Time magazine’s 10 Questions feature is directed to Stephen Hawking. Predictably, the first one concerns God. “If God doesn’t exist, why did the concept of his existence become almost universal?” a reader asks. I was less concerned with the answer than with the implications of the question itself. The very question represents a paradigm shift. Time was, such questions were directed to local clergy. The minister had the answers. To be sure, many millions, if not billions, of people regularly rely on their clergy for divine guidance. I used to teach clergy, so I am wary. Today, however, we need to know if all the answers fit. To find out if God exists, ask a scientist.

Theologians have earned their reputation as inscrutable doyens of the unspeakable. I have been involved in higher education in the field of religion for nearly twenty years and when I read theologians I am left scratching my head and asking “what?” Erudite to the point of being obtuse, the issues and methods of theologians address the unknowable. Much of it is idle speculation. The specialists, however, must earn their keep. Deans are impressed by what they can’t understand. God himself, I’m sure, wonders what some of it means. Is it any wonder that the average citizen would rather ask Dr. Hawking than ask some obscure theologian?

Religion and science are bound to bump at the borders like the parallel universes of string theory. Both are concerned with explaining things. Science has a proven track record of presenting verifiable results while theology has produced a poke full of intangibles. I am the first to admit to being a working-class Joe who has no special knowledge. What I’ve learned has come from the many classes I’ve endured and the books I’ve read. As far as I can tell, none of it comes directly from God. In my mind’s eye I reverse the situation. I see a popular theologian, take your pick (I have trouble conjuring the moniker of a household-name theologian), being featured in 10 Questions and the first query being, “What is M-Theory?” I can imagine the convoluted answer.

All You Zombies

Not being a cable subscriber bears a burden all its own. Not only would paying the extra monthly fees for television prove a hardship, but the constant temptation to watch it would rate as a deadly sin. So on this “All Saints Day” I find myself wondering if the world is still out there after last night’s much-touted “The Walking Dead” premiere. The new AMC series has been written up in local papers and this week’s Time magazine. The latter calls it “a zombie apocalypse.” The fascination with zombie goes beyond holiday-fueled monsters. As James Poniewozik states in his Time article, zombies symbolize society’s insecurities: pandemics, terrorism, economic instability. The unrelenting undead remind us that death is perhaps not the worst thing to fear.

The religious side of this trend is fascinating. Revenants have no place in traditional Christian, Jewish, or Muslim theologies. Perhaps the closest semi-sanctioned version is the golem, a soulless protector of persecuted medieval Jewish communities. Traditional zombies are inextricably connected with magic, a means of manipulating the physical world through supernatural means. Like modern vampires, modern zombies have shifted from supernatural to biological, or at least scientific-sounding, explanations. Even Night of the Living Dead had an errant satellite to blame. The zombie has been reborn in a secular context, making it safe for religious believers to add it to their repertoire of fictional ghouls. And yet, the religious aspect has not completely vanished. The “apocalypse” that accompanies “The Walking Dead,” whether it is Armageddon, 2012, or Ragnarok, is a religious concept. Humans simply can’t face the end of the world without religious implications.

Audiences feeling a little let down after October’s terminal scare-fest, however, might find some cheer that Halloween is an end, but also a beginning. It is the start of the darkest time of year. Very soon not only do we drive home in the dark, but light will not have dawned by the time we start the car for work. In northern reaches of the globe, people can’t help but feel a little stress at finding our accustomed visual assessment of our world a little bit impaired for months at a time. And when we see that shoddy-clothed stranger straggling along in the half-dark, it may be time to remind ourselves that despite the naturalized zombie, there are still those who prey on their fellow humans. They may not be the undead. They may dress well and drive expensive cars and live off what they can legally draw from that stranger on the street. They may be the true harbingers of the apocalypse. They are the ones we should really fear.