This week’s Life section of Time magazine features an issue that yet again raises the questions of definitions and who decides on correct religion. The feature by Tim Padgett entitled “Robes for Women” demonstrates the conflicted nature of religious authority. With the Vatican claiming women have never been priests, but historians questioning the assertion, the salient point is who has the right to decide. And what is lost, if such a change were to take place. Tradition is not threatened by change – it always stands sentinel over the past, but no religion remains unchanged for any length of time. It is not biblical authority that is lost either. Any religious body whose scriptures state, “call no man on earth your father,” yet which addresses its clergy by the title “Father” clearly possesses the casuistry to get around other biblical injunctions. What is lost is male power.

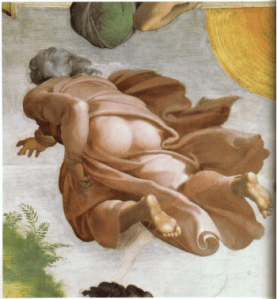

No matter how vociferous theologians may be concerning the genderlessness of God, the default male image seems deeply embedded in the human psyche. One of the most ancient and pervasive of mythological themes is the search for the father. The loving mother is the one who stays near and raises the child while the father leaves to make provision, or for reasons less wholesome. At some level we know that the deity portrayed by Scripture and tradition is male, a father who is difficult to find at times, particularly times of need. This archetypal image is not an excuse not to re-envision a genderless deity, but it underscores what generations of human experience has taught us. Referring to God as father and mother only complicates the matter by throwing into the mix all aspects of gender complications. Can humans even truly worship a god without gender?

If the Womenpriests movement succeeds, as no doubt it should, there will always remain a group who will not accept their authority. My experience at Nashotah House taught me that some prejudices are so deeply rooted that they are no longer even recognized by those who hold them. Wild examples of theological gymnastics were paraded before me as to why women should not hold priestly office. And like Nashotah House reveals, if women are finally accepted by Rome, others will split away and both sides will lay claim to the true faith. There will be no convincing either that the other is correct. The history of Christianity has taught us this sad truth. Current estimates suggest there are some 38,000 different Christian denominations. This is the common fate of all religions who claim to have exclusive access to the single, unambiguous truth.