The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the ancient documents still widely recognized, at least by name. Many introductions to literature, or the western canon, refer to it. It is, in some senses of the phrase, the world’s first classic. I’ve read Gilgamesh enough times not to know how many times it’s been. During my doctoral days I was focusing on the literature of neighboring Syria (long before it was called “Syria”). As an aside, Syria seems to have gotten its name from the fact that non-semitic visitors had trouble saying “Assyria” (which was the empire that ruled Syria at the time). Leaving off the initial vowel (which was actually a consonant in Semitic languages) they gave us the name of a country that never existed. In as far as Syria was a “country” it was known as “Aram” by the locals. Back to the topic at hand:

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the ancient documents still widely recognized, at least by name. Many introductions to literature, or the western canon, refer to it. It is, in some senses of the phrase, the world’s first classic. I’ve read Gilgamesh enough times not to know how many times it’s been. During my doctoral days I was focusing on the literature of neighboring Syria (long before it was called “Syria”). As an aside, Syria seems to have gotten its name from the fact that non-semitic visitors had trouble saying “Assyria” (which was the empire that ruled Syria at the time). Leaving off the initial vowel (which was actually a consonant in Semitic languages) they gave us the name of a country that never existed. In as far as Syria was a “country” it was known as “Aram” by the locals. Back to the topic at hand:

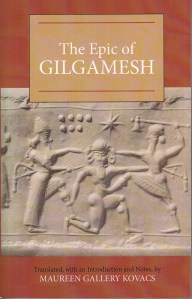

Although the story of Gilgamesh may be timeless, translations continue to appear. It won’t surprise my regular readers that I’m a few behind. I finally got around to Maureen Gallery Kovacs’ translation, titled simply The Epic of Gilgamesh. Updating myself where matters stood in the late 1980s, it was nevertheless good to come back to the tale. For those of you whose Lit 101 could use a little refreshing, Gilgamesh was a Mesopotamian king who oppressed his people. (And this was well before 2017.) The gods sent a wild man named Enkidu as a kind of distraction from his naughty behaviors. In an early example of a bromance, the two go off to kill monsters together, bonding as only heroes can. They do, however, offend the gods since hubris seems to be the lot of human rulers, and Enkidu must die. Forlorn about seeing a maggot fall out of his dead friend’s nose, Gilgamesh goes to find the survivor of the flood, Utnapishtim, to find out how to live forever. He learns he can’t and the epic concludes with a sadder but wiser king.

The fear of death is ancient and is perhaps the greatest curse of consciousness. When people sat down to start writing, one of the first topics they addressed was precisely this. Gilgamesh is still missing some bits (that may have improved since the last millennium, of course) but enough remains to see that it was and is a story that means something to mere mortals. Ancient stories, as we discovered beginning the century before mine, had long been addressing the existential crises of being human. Thus it was, and so it remains. No wonder Gilgamesh is called the first classic. If only all rulers would seek the truth so ardently.