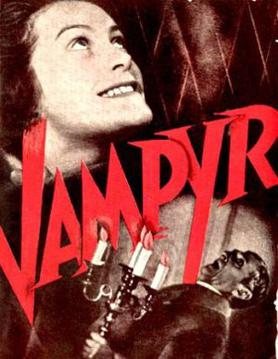

Early movies are fascinating. I learned of Vampyr, a 1932 production by Carl Theodor Dreyer, from Raymond T. McNally and Radu Florescu’s In Search of Dracula, where they praise it. I’d never heard of it before. There are probably a few reasons for that. One is the movie was considered not very good when it was released, and it never garnered much of a reputation. Another is that the original prints, including the soundtrack, had been lost. Three language versions had been shot—German, French, and English. Since this would obviously lead to lip-syncing problems, there is very little dialogue. The movie as it exists today is accessible in the German version, and it tends to fall into that category that includes work by directors such as Ingmar Bergman and Stanley Kubrick. It has art house elements and the story requires some pondering. It isn’t bad, although in today’s viewing culture, it might seem dull.

It is a vampire story based on the works of Sheridan La Fanu. The star, and also financier of the movie, was an actual Baron from France (in real life), Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg. He plays a student of the occult who happens upon a gentry-class family plagued by a vampire. Interestingly enough, this kind of character is distinctly Lovecraftian, and there is a passing resemblance between de Gunzburg and H. P. The acting isn’t great, but the story is good. It includes shadow people who assist the vampire—a female, in this case—and a kind of mad doctor who helps her reach her victims. The occultist and the household servant of the gentry family locate the vampire’s grave and stake her. And in a scene that may have inspired Witness, they suffocate the mad doctor in the bin of a flour mill.

Like many vintage movies, Vampyr has received a more positive reevaluation over time. While some consider it great, the consensus seems to be more at the “very good” level. It is an early vampire movie, apparently filmed before Tod Browning’s Dracula. While not scary by today’s standards, there are some definitely creepy scenes. Particularly when the elder daughter of the gentry family begins to become a vampire, leading to some quite effective facial expressions. McNally and Florescu weren’t film critics by any stretch but they felt that, up to the early seventies, this was the best vampire movie made. I might not go all the way with them, but I would suggest it is certainly worth viewing by those who like old cinema, and who appreciate vampire stories.