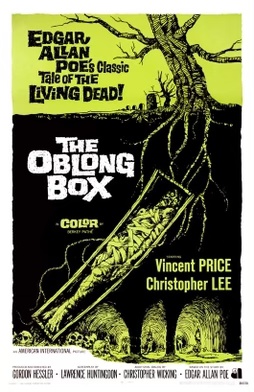

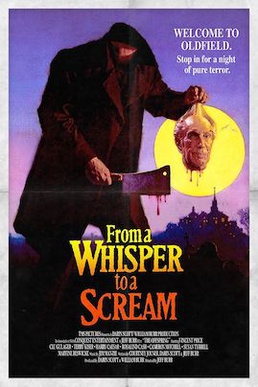

Curious to finish out the “Poe Cycle” of American International Pictures, I looked up The Oblong Box. The only thing similar to Poe’s tale is the title, as viewers must’ve come to have expected even in 1969. Poe was the marketing to sell the film, but not much more. Okay, the theme of premature burial has Poe’s fingerprints all over it, but that’s not part of his story “The Oblong Box.” Now, as for the movie, it has several subplots and a pretty high body count. Its ending isn’t really explained, but after starting out as seeming racist, it comes out justifying the actions of the Africans at the beginning. In the middle it’s a muddle. Pacing is completely off and some sub-plots, such as the police investigation, are summarily dropped. Apart from the positive view of Black people, which is important, the film is a confusing criss-cross of unsavory motivations.

The Markham brothers own an Africa plantation and the trampling of a slave by a horse leads to revenge on the part of the slaves. The scarred brother, Edward, is driven insane and he escapes his brother Julian’s care by being buried alive. Grave-robbers, however, want him so Christopher Lee can experiment on his corpse. Edward escapes again and dons a scarlet mask, but his insanity leads him to kill a variety of people, looking for the witch doctor who can cure him. Meanwhile, an unscrupulous lawyer is cashing in on the brothers’ wealth but ends up being killed by Edward. There’s a rather pointless bar fight, and, after killing Lee, Edward and Julian finally face off with Edward getting shot but biting his brother before he dies. The witch doctor raises Edward from the dead, buried in his coffin, and Julian now has his brother’s scarred face (and presumably, his insanity).

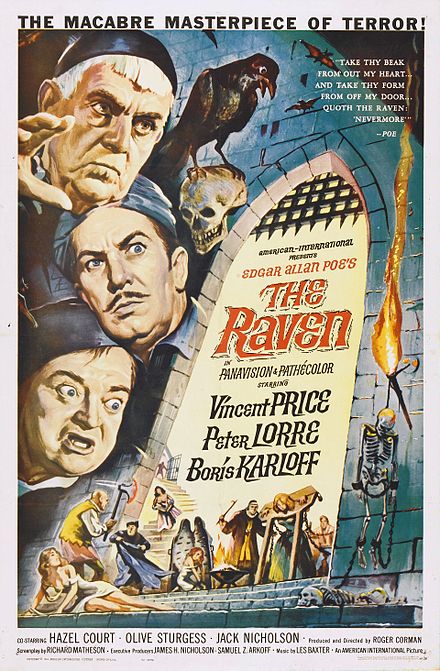

The movie was the first to feature both Vincent Price and Lee. The film had a change of directors, pre-production, and a script that was added to by another writer. The plot verges on tedious and it’s difficult to feel sympathy for any of the characters, apart from the women, who don’t seem out to hurt anyone. Price (Julian) also plays a “good guy” until the reveal near the end, but Edward dominates the screen time, all the while wearing a mask. The “Phantom of the Opera” reveal is shot in the dark, however, and the results are not so grotesque. And those who’ve read Poe’s story wonder where the ship might be. This is the only Poe Cycle film not directed by Roger Corman, and he, as well as Poe, are both missed.