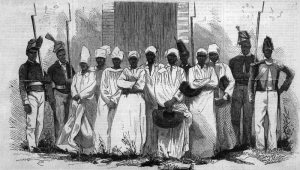

Do you know the difference between “Voodoo” and “hoodoo”? Well, The Skeleton Key does. This is a movie I watched at the recommendation of a friend. I get a sense—perhaps based on stats, or maybe lack of engagement—that you folks that kindly read this blog generally don’t watch the same movies that I do. Nevertheless, I hesitate to give away spoilers for films I think more people should see. So we’ll explore hoodoo instead. But first, I can give you the basic idea of the film, in case you’re one of the few who takes recommendations from this blog. Caroline is a young hospice nurse who feels guilty about not being present when her father died. She gets a job with a couple in a decrepit southern Louisiana mansion where he’s dying and she’s doing fine.

Caroline isn’t from the south, however, and she senses that something’s not right. A modern girl, she doesn’t believe in the supernatural, but she slowly becomes convinced that something strange is happening in the house. That something turns out to be hoodoo. Critics weren’t particularly kind to the film when it came out in 2005, but I found it moody and engaging. There were some exciting scenes and I enjoy haunted house movies generally. And this one uses a lot of religious imagery, even though hoodoo is better thought of a form of spirituality than a formal religion, like Vodou is. The movie defines the difference as one between religion (Vodou) and magic (hoodoo). There’s some truth in that, but scholars are inclined to class magic and religion together.

Hoodoo consists mainly of folk spirituality that involves some magical beliefs. Like Vodou it’s of African origin, mixed with the cultures experienced by slaves in the new world. Unlike Vodou, it doesn’t have any kind of formal structure. The reason it’s treated with suspicion, in general, is because it’s of African origin and doesn’t fit well with northern European ideas of the way the world works. Skeleton Key makes pretty heavy use of hoodoo as a plot point and it isn’t alone in using African traditions to inculcate horror. The Believers, many years back, did a similar thing with brujería. Although these folk traditions are generally kept separate from “religion,” they tread similar ground with similar aims. And since they’re “foreign”—at least to button-down white Christianity—they’re treated with utmost suspicion. I think Skeleton Key handles this well, and if you’re one of the few who takes recommendations on movies, I’d suggest it’s worth seeing.