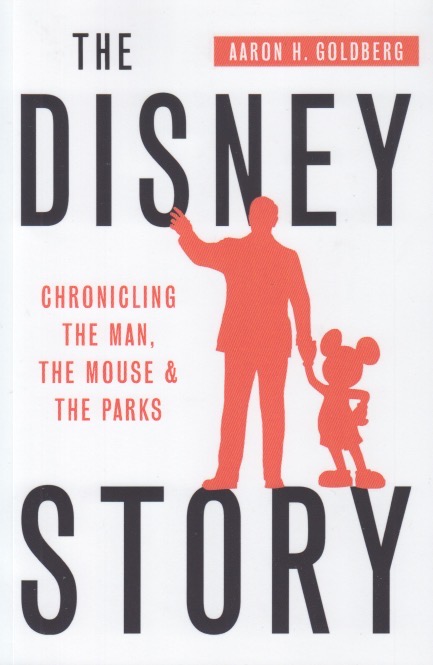

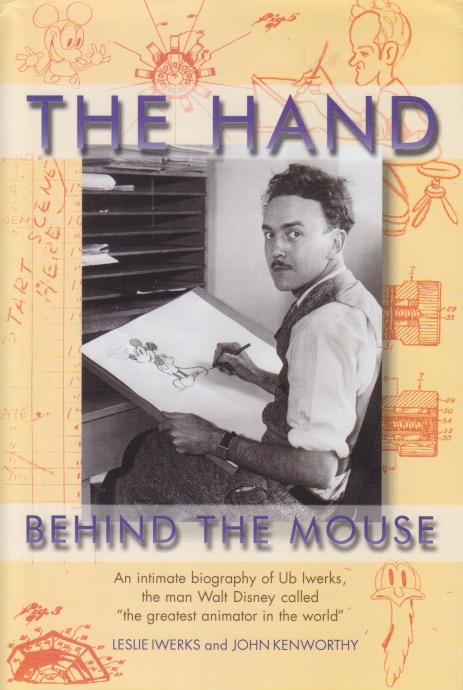

What’s the earliest Disney movie you remember seeing? If you’re my generation this will’ve likely been in a theater since home recording wasn’t a thing yet. I suppose it could’ve been on Disney TV, but if it was a new movie you wanted to see it just after it was out. Mine was The Jungle Book. Or, at least that’s how I recollect it. Reading about Ub Iwerks made me curious about Disney so I decided to read Aaron H. Goldberg’s The Disney Story. The subtitle, Chronicling the Man, the Mouse and the Parks, gives you an idea of what it covers in more detail. Goldberg’s upfront in letting the reader know that newspapers and period media are his main sources. The book is arranged chronologically. It makes for an interesting story but I personally have never been tempted by a Disney theme park—quite a bit of the book discusses these—although there was that one time…

It was back in 1998—what a different world then! Pre-9/11, pre-Trump, pre-pandemic. I was still teaching at Nashotah House. The American Academy of Religion and Society of Biblical Literature held their annual meeting in Orlando, on the Disney campus. The experience wasn’t a good mix. Academics and cartoon characters just don’t—wait, maybe they do. In any case, you had to eat at the Disney estates, although you could sleep in an off-site hotel, that was a considerable shuttle ride away. And no bars. I did meet David Noel Freedman there. It was in a room painted like the inside of a circus tent. A strange place for a meeting of such gravitas to a still young scholar.

The point is, Walt Disney affects all of our lives. He was a self-made man, but he had lots of help. He didn’t live to see Walt Disney World (that’s the one in Florida) open, but he died knowing just about every child in the country recognized his name. I never considered myself a Disney fan. Yes, I watched a few of his movies and watched his Sunday evening television show, but I preferred Bugs Bunny and the Warner Brothers’ crowd. Growing up with television you had your loyalties. Still, we were well aware of Disney and especially his movies. We couldn’t afford to see all of them, not by a long shot. And those we did see were at the drive-in where kids could hide under a blanket in the back seat to economize a bit. Still, we were infected. Everyone was.