Not being an art critic, I’m in no place to analyze John Quidor’s The Headless Horseman Pursuing Ichabod Crane. Having written a book about Sleepy Hollow, however, there are a few things I might point out. I should begin by noting that this post was spurred by a jigsaw puzzle. Normally I only work on said puzzles around Christmas time. Several years ago friends told us about Liberty Puzzles. They’re made of wood and are heirloom quality. My wife took the hint and she generally orders one, on behalf of Santa Claus, each year. We have a few now but since we only do them once a year (and usually only one of them at the time), I had forgotten that we had a Liberty Puzzle of Quidor’s painting. The original is located in the Smithsonian and I really didn’t discuss it in my book. The painting is dated 1858, almost forty years after the publication of Irving’s tale, but while Irving was still alive (he died the next year).

The painting is correct in displaying a pumpkin that isn’t a jack-o-lantern and it presents one of the obvious difficulties of painting a nighttime scene. The painting is fairly dark. One of the benefits of working on a puzzle like this is you look closely at the scene. My first thought was that it seems odd that the lightest part of the painting is Gunpowder’s rump. Next is the path. The path draws the viewer’s eye back to Gunpowder and an understated Ichabod Crane. I realized that the lighting is meant to reflect the moon’s rays, as the orb is just peeking through the clouds at the upper left. And, of course, Quidor was not painting from real life. On the right lie some small buildings, including the Old Dutch Church. The Headless Horseman blends into the dark, which is exactly how Irving describes him in the story. There’s no bridge, however, at least not yet. All of this matches the wording of the legend.

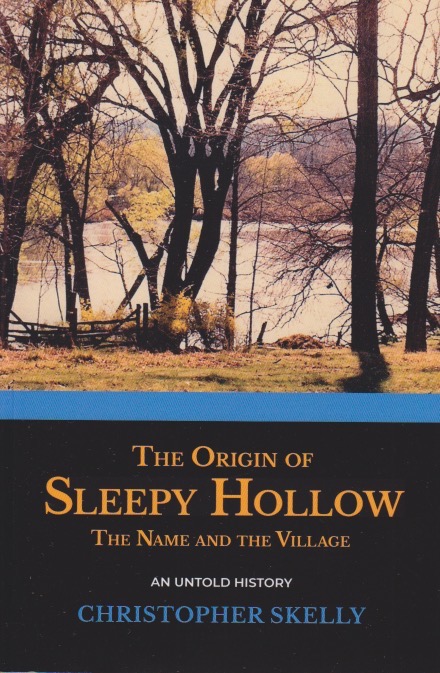

Quidor painted mostly scenes from Washington Irving’s works. Having been born in Tappan, during Irving’s lifetime, that makes sense. He was also painting before the Disney cartoon came out. One of the cases I make in Sleepy Hollow as American Myth is that the image most Americans have of the story comes from Disney. The painting has no sword, and indeed, neither does Irving. The one dramatic effect Quidor allows is the raising of the pumpkin before the bridge. That takes place later in the chase. In a sense this painting is perhaps the most authentic visual interpretation of Irving’s story before it made the transition to celluloid. It’s puzzling.