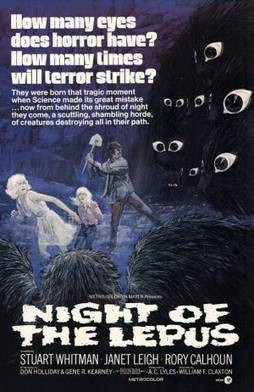

I was quite young when I saw Night of the Lepus for the first time. Well, I had to have been at least ten, but when I recently sat down to watch it only one or two scenes looked familiar. Like most poorly done horror films, Night of the Lepus has gained a cult following. The story is loosely based on Russell Braddon’s comedic novel Year of the Angry Rabbit. Without the comedy. Or at least without intentionally being funny. In an effort to control rabbit overpopulation in Arizona, a new virus is released into the population. Instead of killing off the bunnies, it makes them grow as large as wolves and become carnivorous. They go around attacking people with big, nasty, pointy teeth (to be fair, Monty Python and the Holy Grail wouldn’t be out for three more years).

Night of the Lepus was criticized for not being scary at all—a cardinal sin for a horror film. I was kind of embarrassed when my wife walked in and found me watching it. Nostalgia can do funny things to a person. It is almost painful to watch the public officials make such obvious missteps each time they start to get an idea of what’s happening. They’re almost as imbecilic as the Trump administration was. Meanwhile rabbits are hard to make scary. Perhaps William Claxton should’ve read Watership Down. Ah, but Richard Adams’ classic was only published in 1972, the year the movie was released. What was it about the mid-seventies and rabbits?

Part of the problem is that Night of the Lepus takes itself seriously without the gravitas required to do so. Who can believe actual rabbits are vicious when, to make them monstrous, the movie simply shows rabbits against miniature scenery? Their human handlers occasionally smear their mouths with red, but a rabbit doesn’t appear cunning and vicious. And to get them to attack people they had to use human actors in rabbit suits. I’m a fan of nature going rampant as a vehicle for horror. Hitchcock’s The Birds did it effectively. So, I’m told, did Willard (which is remarkably difficult to access with HBO never having released it onto DVD). The seventies were when ecology began to be recognized as perhaps the most important of global issues. Half a century later we’re still struggling to reconcile ourselves with it. Meanwhile the rabbits have begun to appear in our back yard. They may nibble our perennials, but I’m not afraid. At least as long as they don’t watch Night of the Lepus and start to get some ideas.