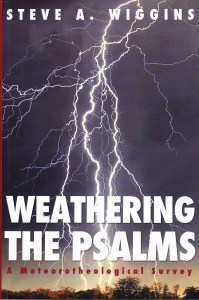

While in a used bookstore recently, I was going over the science titles. I like to read accessible science since I often find it approaches religious ideas in secular terms. Once in a while even the terms of these disparate disciplines coalesce. I spied a volume on the top shelf titled The Mercy of the Sky. The spine showed a purplish cloud-bank, and the very concept set me wondering. We’d just been through a bomb cyclone the day before with wind bellowing through our apartment. Many trees were down and power was out for several people I’d overheard talking that day. I stared at the spine, thinking perhaps this would be a good follow-up to Weathering the Psalms, but as I already had books in my hands, and since I’m not the tallest guy around, it seemed beyond my reach. Of course, after I left I thought more about it.

The previous day’s nor’easter had revived that sense of a storm as divine anger. Strong winds, my wife commented, are generally disturbing. They make it difficult to sleep. It’s hard to feel secure when the heavens are anything but merciful. Although the wind is easily forgotten, it’s among the most easily anthropomorphized of natural phenomena. And it’s ubiquitous. Everything on the surface of the earth is subject to it. Indeed, the atmosphere is larger than the planet itself. Is it any wonder that God has always been conceptualized as in the sky? The quality of the mercy of the sky, we might say, is strained.

Danger comes from the earth below us, the world around us, and the realm above. Like our ancient ancestors staring wonderingly into the sky, it is the last of these that’s most to be feared. The wind can’t been seen, but it can be felt. It cuts us with icy chills, drenches us with dismal rain, even flings us violently about when its anger compresses it into a tight whirl. We can’t control it. Unlike other predators it requires neither sleep to refresh nor light to see. Its rage is blind and it takes no human goodness or evil into account. After a great windstorm, the calm indeed feels like a mercy. Elijah on Mount Sinai stood before a mighty wind, tearing the land apart. It was the still, small voice, however, that captures his imagination. There’s a calm before the storm, but it is the stillness in its wake that most feels like the mercy of the sky.