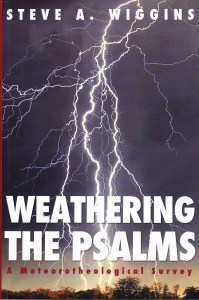

A neologism is an invented word. Of course, it is impossible to be certain about the origins of many words, and even the many neologisms attributed to William Shakespeare may have been overheard by the bard at the local pub. Still, one of the things I sometimes dream of is inventing a word that will come into wide circulation. I think it must be easier to do in fiction than in non-fiction writing. When I first wrote my book, Weathering the Psalms, I chose what was, at the time, a neologism for the subtitle. “Meteorotheology” was a word I’d never read or heard before and, quite frankly, I’m not sure how to pronounce. Although the world-wide web existed when the book was written, scholarly resources were still few, and tentative. Amazingly, that has changed very rapidly. Now I’d be at a loss to find most basic information if I were isolated from a wifi hotspot. In any case, the web has revealed that others beat me to it when it comes to meteorotheology.

I suppose that some day, when I have free time, I might go back and see if I can trace the web history of the word. It is used commonly now to refer to God taking out wrath on people through the weather. For example, when the Supreme Court decision on the legality of gay marriage was handed down this summer, there were various websites—more popular than mine!—asking a “meteorotheological” question: when was God going to send a hurricane to punish the United States for its sin? These were, as far as I can tell, all tongue-in-cheek, but there can be no question that some people treat meteorotheology that way. It is a sign of divine wrath. My own use of the word had a wider connotation. When I was invited to present at talk at Rutgers Presbyterian Church in Manhattan a few weekends ago, I was reminded of my line in the book: “To understand the weather is somehow to glimpse the divine.”

That’s an idea I still stand by, but it is difficult to move beyond. What exactly does the weather say about beliefs in the divine? There’s plenty of room for exploring that. I know that when I walk outside to fetch the paper on a clear fall morning when the moon and stars are still out, I know that I’m experiencing a kind of minor theophany. The brilliant blue of a cloudless October sky can transport me to places unlike any other. What exactly it is, I can’t lay a finger on. That’s why I came up with the word meteorotheology. I many not have been the first person to use it. I may even be using it incorrectly. But the weather, in my experience, has many more moods than just anger. Any autumn day is enough to convince me of that.