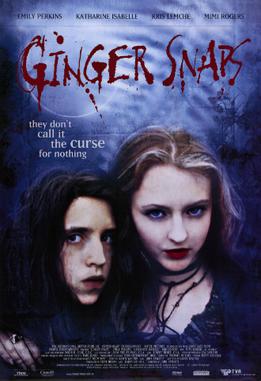

I’ve known about Ginger Snaps for years but the reason I finally watched it was a rainy fall weekend. The kind of day that suggests imminent winter and you wish that you had a fireplace instead of waiting on the furnace guy to check everything out for another year. Surprisingly, in my experience, there aren’t many movies that capture that mood very well. The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane is one of the best. But movies new to me give me topics for blogging, and so I watched Ginger Snaps. It’s not a typical werewolf movie. It’s become a cult favorite over the years since it didn’t get much of a box office boost. It’s smart, and sad, and moody. And, as is becoming more important to me, well acted.

Brigitte and Ginger are teenage sisters, 15 and 16 respectively. They share a room and morbid interests. Their affluent, suburban parents just don’t understand them. They’re ostracized at school. Then Ginger gets bitten by a werewolf. The plot is a coming-of-age story for women, and it has attracted feminist interest over the years. The sisters are devoted to each other because both are pariahs and, well, sisters. This begins to change when one of them becomes a monster. But only to a degree. Brigitte is determined to stick with her lycanthrope sibling, and tries to cure her. There’s quite bit of dark humor along the way but this is pretty effective body horror. Making it about growing up adds an emotional poignancy to the story.

Werewolves have always been my favorite classical monster. Ginger Snaps made me realize that it’s almost always a guy problem, however. Men are the ones struggling to keep the beast inside. Having this apply to a young woman throws into relief all the uneven standards society harbors. Some exist for pretty obvious historical reasons, but others are matters of convention, often religious in nature. Religion is pretty much absent from this movie, however. Lycanthropy is transmitted like a virus and you don’t need silver bullets to stop a werewolf. This is a world, in fact, where teens have to try to figure out their own way because parents are too distracted with their own problems. It is a kind of modern parable, but without a religious angle. The girls are conflicted about what’s happening to Ginger. She enjoys the power but fears the consequences. It is a good Halloween movie, but mostly it’s about growing up, whatever that may be like.