I’ve been thinking about brains (is there any more existential thing to do?). Reading a book this week about the mind (see Thursday’s post) probably has something to do with it. And also having finished a book on zombies maybe contributes as well. You see, I find it strange when scientists assume that we can figure out all the answers with our limited brains. Although we are endlessly fascinated by them, neuroscientists have long noted that they do have weaknesses—they (brains) are easily fooled, and, for those who find no room for the mysterious in the universe, we’ve made up gods to keep us company. We know that relative brain size—relative to body mass, that is—is a large factor in intelligence, but we seem not to imagine the possibility of larger brains than those we carry around. I suppose it’s not without reason that alien brains are disproportionately larger than our own, according to the standard image of the “grays.” We don’t like to think there’s something smarter than us hanging around. It’s a frightening thought.

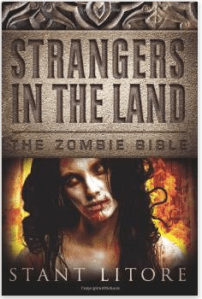

On the more earthy side, brains have been the usual fare for zombies in one sub-division of the zombie movie neighborhood. George Romero gave us flesh eating as a paradigm, but eventually zombies settled on brains. This was on my mind as I finished the epic Strangers in the Land that Stant Litore kindly sent me in Kindle form. I’d read What Our Eyes Have Witnessed on my own, and the author wanted me to read more. Litore’s zombies are more in the canonical Romero sector—they eat flesh and their bite conveys zombiehood. Strangers in the Land takes its base story from the book of Judges. Only Deborah becomes a zombie slayer. Brains aren’t eaten here, but they must be destroyed for a zombie to—what? Redie? Full of colorfully drawn characters, the story rambles through the countryside of ancient Israel, plagued with zombies. It is the brain that keeps a zombie going.

On the more earthy side, brains have been the usual fare for zombies in one sub-division of the zombie movie neighborhood. George Romero gave us flesh eating as a paradigm, but eventually zombies settled on brains. This was on my mind as I finished the epic Strangers in the Land that Stant Litore kindly sent me in Kindle form. I’d read What Our Eyes Have Witnessed on my own, and the author wanted me to read more. Litore’s zombies are more in the canonical Romero sector—they eat flesh and their bite conveys zombiehood. Strangers in the Land takes its base story from the book of Judges. Only Deborah becomes a zombie slayer. Brains aren’t eaten here, but they must be destroyed for a zombie to—what? Redie? Full of colorfully drawn characters, the story rambles through the countryside of ancient Israel, plagued with zombies. It is the brain that keeps a zombie going.

While I have to stand by my recurring assessment that the zombie is a hard sell in novelistic form (here goes my mind again! Reading a book gives your brain too much time to focus on the utter impossibility of bodies missing organs or vital tissue to move, or “live,” even with a brain) Litore is onto an interesting idea here. Looking at it metaphorically (as surely he intends it) helps. Perhaps I just miss the lumbering revenants of Return of the Living Dead calling out “Brains! Brains!” The Bible, however, is endlessly open to reinterpretation. What Our Eyes Have Witnessed was post-biblical. This current installment moves us into the realm of reception history. I’ve been researching reception history and the undead for a few months now. I have some conclusions to share in an academic paper a few months down the road, but for the time being, I’m still trying to figure out brains. Or maybe I’m just out of my mind.