Winter Term is underway, and one of the first aspects of the Bible I discuss with students is the fact that the Bible was a book that was compiled instead of written. In our society we are used to the concept of the Bible as a document that is unified by divine authorship, often forgetting (or ignoring) that none of the authors was intending to write a book with the tremendous authority the Bible now enjoys. Students ask how the Bible came to be; it was a process of gathering material widely utilized in Judaism. No one knows the actual composition history of the Torah, but after the Pentateuch got the process rolling, scrolls were gathered in collections and added to the Bible en masse. By the end of the first century of the Common Era, we had a Hebrew Bible.

Sometimes this historical reconstruction is a hard-sell to members of a society where a divinely written book is accepted alongside sub-atomic particles and super novas. Despite the technological sophistication that accompanies growing up in our engineered world, students are often ill-equipped to accept the Bible as a product of human exploration. The writers, whoever they were, traveled this same path of discovery that we continue to tread. They wrote down their hypotheses, based on their experience, just like modern people continue to do. The difference is they did this a very long time ago.

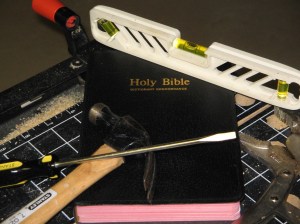

Those books that were selected for inclusion in the Bible became the defining documents of western civilization. Even though there is now an international space station orbiting out of sight above our heads, and even though quarks, leptons, and bosons fly out of cyclotrons large enough to encircle most small towns, God still holds a quill pen. The fixation just after the age of cuneiform is a curious one. If only God had held out for the invention of the Internet, the compilation of the Bible would have taken a very different course, I suspect. Instead of beginning its title with the word “Holy” it would more likely have commenced with “Wiki.”