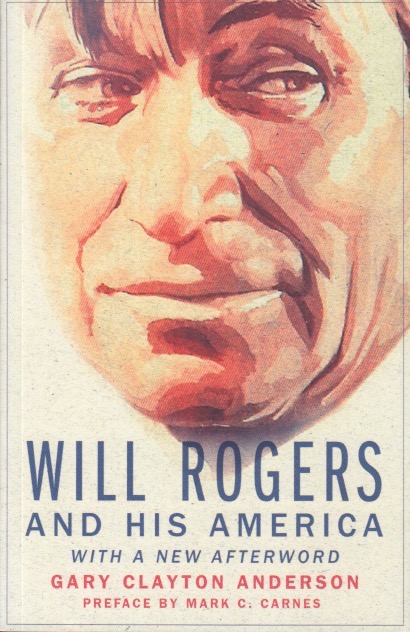

I’m not really interested in politics. Powerful people deciding the fate of the rest of us seems inherently depressing. We could use a good laugh. I’ve been curious about Will Rogers for some time now. He’s a name that everyone in my generation seems to recognize but few people know anything about him, beyond some of his famous quips. So I read Gary Clayton Anderson’s Will Rogers and His America. It was an eye-opening experience. Rogers died in 1935, the year my mother was born. What a difference less than a century can make! At the time of his death he was one of the most famous people in the country, personal friend of U.S. Presidents, an international traveler, and widely syndicated newspaper columnist. He was also a film actor and comedian. When he traveled internationally world leaders gladly met him. Not bad for a poor boy from Oklahoma.

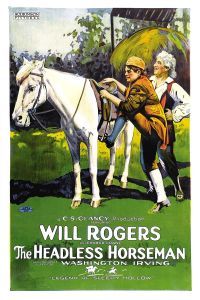

Anderson’s book is a good introduction to who Rogers was, but it does tend to focus on the politics. Arguably that’s where one’s greatest impact in life might reside. Still, there’s a lot more to an individual than politics. I’m curious about Rogers’ career as an entertainer. He started out as a Vaudeville roper—literally, a rope act. His noted wit, however, made him famous. At various points he was one of the highest paid entertainers in the country. His sympathies, like many of us born in humble circumstances, tended to be with the average person who, it seems, is always struggling against an economy that favors the wealthy. See? There I’ve done it myself, gone and got political. It’s difficult to avoid.

Perhaps the most widely read columnist in the country, who influenced political opinions and could rake in the money at just about any form of comedic enterprise, Rogers nevertheless faded from view after his death in a plane crash. He was part American Indian. He never completed college. He was homespun and yet influential around the world. Fame comes with no guarantees, of course. I guess it would be helpful to know what Roger’s motivations were. Was he, like most people, simply trying to secure his future for himself and family? Was he trying to change the world? Can anyone manage to do that for very long before things come along and everything’s suddenly different? (Think AI, for example.) I’m glad to have met Will Rogers through Anderson’s book. Even though I’m not really interested in politics, I learned something about them too, along the way.