This blog is the closest thing to a diary that I keep anymore. It’s also the place where I remind myself when I read a book or saw a movie. I started this blog (actually, my niece did, but I started putting content on) about a decade-and-a-half ago. Most of the books I’ve read since then (but not all), have been featured here. It didn’t start out that way with movies. I watch a lot of films. The other day I was wondering when I first watched The Exorcist. I figured that it must’ve been something I’d blogged about, knowing me. It could be that I watched it before 2009, or it could be that the search function on WordPress doesn’t allow me to find the post, if it exists. You see, I don’t know what else to search for beyond “The Exorcist,” because I can’t recall what I might’ve written about it. If I did.

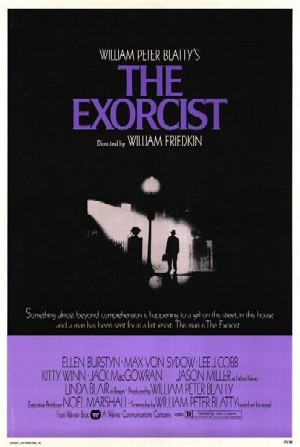

So, in case I haven’t, I do want to say a bit more about that experience. I was only eleven when the movie was released. Three movies that I grew up terrified to see were Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and The Omen. I finally saw them as an adult. Since it was the DVD era (preceded by the VHS era, and followed by the Streaming era—all within about three decades) I bought the disc. In all likelihood this was at FYE, which used to be a thing, just like Blockbuster before it. Of course by the time I sat down, trembling, to watch it I’d seen many clips, stills, and parodies. Still, I was afraid. The movie, some thirty years old, lived up to its reputation. I was left trembling more than when I started.

Many books have been written about The Exorcist, and although people sometimes laugh at it today, most horror fans I know still speak of it with reverence. This movie changed horror. It also changed demons. Today what we believe about demons derives largely from this movie. Its explanatory value is that it offers somewhere to turn when nothing else works. Religion as a last resort. And, ultimately, religion works where everything else fails. It is possible, that somewhere in this sprawl of a blog, that I wrote first impressions of seeing it. It would’ve been 2009, or perhaps I saw it as early as 2006. I was struggling with my own demons then. And, as often happens in such cases, precisely when things happened can be a little difficult to determine.