What with all the Bible-trumping going on these days among the desiccated religions right, I thought it might be helpful to turn back to the Good Book itself. Since we have a self-proclaimed stable genius in house there should be nothing to be concerned about. What, me worry? Right, Alfred? One part of the Bible frequently cited by fundies and others who want to appear chic is the “Wisdom literature.” Although the category itself has come under scrutiny these days it’s still safe to say that Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes have quite a bit in common with each other. Proverbs is a repository of pithy aphorisms. Indeed, it can sound downright modern in many respects (but hopelessly patriarchal and chauvinistic in others, unfortunately). One of the things Proverbs does is condemn fools. The sages of antiquity had no time for stupidity. Remember, we’ve got a stable genius—don’t worry.

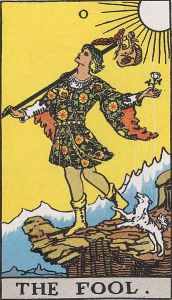

Like Laplanders and their many words for “snow,” the book of Proverbs uses several terms for fools. There is, for instance, the innocent fool. This is the person who simply doesn’t know any better. Often it’s because of inexperience. This kind of fool can learn from failures and may go on to better things. Far more insidious is the willful fool. This is the person proud of his or her ignorance. Proverbs goes beyond calling such a thing unfortunate—this kind of foolishness is actually a sin. Not only is the arrogant fool culpable, they will be judged by God for their love of stupidity. As a nuclear super-power it’s a good thing we have a stable genius with the access codes. Otherwise those who thump the Bible for Trump might have a bona fide sin on their hands.

The only kind of fool that’s tolerable in the world of Proverbs is the one that’s able and willing to learn. This means, in the first instance, being humble. Refusing to admit mistakes, forever posturing and preening, this is a certain recipe for incurring divine wrath in the biblical taxonomy of fools. According to biblical wisdom literature, such people get what they deserve. The modern evangelical often has little time for such books. Aside from a misogynistic slur or two, there’s nothing worth quoting from Proverbs that you can’t find in Benjamin Franklin or even in ancient Egyptian records. When you stop to think, however, that the Bible’s said to be inerrant, you’ve must take Proverbs and what it says about fools into account. But then again, what Fundamentalist ever really reads the Bible?