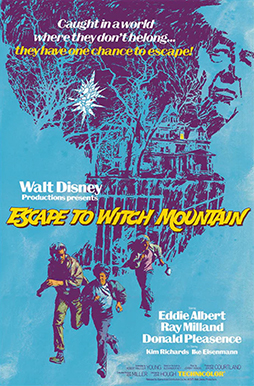

Disney movies—and I still think of Disney primarily as a movie studio—were part of my childhood. A small part, but there nevertheless. We didn’t go to theaters often but we caught some movies on television (do you remember eagerly reading TV Guide to find out what was going to be on that week?). We did watch The Wonderful World of Disney and some of their series—I recall the one ones on Daniel Boone and Davy Crocket. Still, I missed a lot. I didn’t see Mary Poppins, for example, until I was in college. So the other day I got curious about Escape to Witch Mountain. I’d not seen it as a child and never saw any reason to watch it as an adult. I’ve been taking a break from bad movies, and, as it turns out, Disney. So there may be spoilers below, in case you’re waiting to see it.

I didn’t know the backstory or the plot, so seeing this the first time I wasn’t sure what to expect. The movie shows its age (I was a mere lad of twelve when it was released), but the story is interesting. Tony and Tia are adopted but have to be sent to an orphanage. We quickly learn that they have “powers,” and that adults like to exploit such things. A wealthy villain has his fixer pose as their long lost uncle to get them to his house, under his control. The children realize that they must escape to, well, Witch Mountain. Actually, that takes some time and a sympathetic adult who can drive. In the end it turns out that they’re aliens, not witches.

Not cheery like many Disney films, Escape to Witch Mountain, although you know it will end well, has a fair bit of tension. Especially scary is the mob mentality that takes over the locals when they start their literal witch hunt. Armed and dangerous, those who want to preserve the uniformity of small-town mentality are serious about their convictions. As usual, they focus on the enemy without getting to know who, or what, they really are. Obviously, there are larger issues to consider, as there are when anyone has an advantage. But the kids, aliens, are sweet and mean nobody any harm. All they want is to get back to their people. Can humans, however, ever be satisfied knowing that there are others out there more advanced than we are? Perhaps there’s a reason for cover-ups, after all. Disney often says more than it’s given credit for saying. Even if I missed it until now.