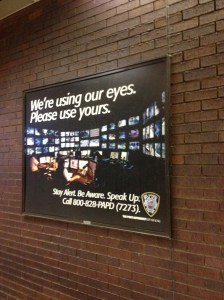

The end of the world, it seems, never goes out of fashion. My wife shared a story on the BBC about CNN (such self-referential media hype may be a sign that society is collapsing already) having a video ready to release for the apocalypse. In a bit of end-of-time sangfroid, it is rumored, CNN’s Ted Turner ordered a last-second video to be made so that loyal CNN viewers would be ushered out with his version of the last word. The media, of course, is a powerful segment of society. Occasionally schools and businesses are shut down due to their meteorological predictions. The media tells us who the experts are, and why we should listen to them. The media provides us with some of the only fact-checked material from far-flung ends of the globe—or even outer space—to which we, the people, would not normally have access. The media, in other words, determines reality.

Meanwhile I wonder, as I often do, what gives those who own media corporations the right to determine reality for the rest of us. For example, if the rumor of Turner’s video is true, what would give the rich and powerful the right to determine what flashes before our eyes as the world winks out of existence? The apocalypse, after all, is a religious concept. Although largely developed from biblical scripts, other religions do occasionally have their end-of-the-world myths, just like most religions have beginning-of-the-world myths. If you have billions of dollars, does that mean you have the right to determine end-times viewing? When money determines the truth, the world has already ended.

Nevertheless, the idea lives on. We are constantly reminded that one or another religious sect has declared that the end is nigh. We’ve heard it so often that we’ve ceased to pay attention. In a world where the media has largely dismissed the rest of the Bible (except when blockbuster movies come out featuring a biblical story) why does Revelation still hold such currency? After all, the apocalypse takes its very name from the final book of the Christian Bible, and without Revelation we might be none-the-wiser about the looming end of all things. Revelation was very much a product of its time. Despite the progress of science and technology that gave us the media corporations we blandly recognize today, we still harbor doubts deep down about the longevity of it all. Even those who write the news look to other media giants to get some hints of the truth. Ironically, they don’t seem to want to ask scholars about it. After all, sensationalism is news. At the end of the world, we really don’t care what scholars have to say, as long as we’re entertained.