I stepped into a devil of a situation. Elevators are strange spaces. Given the choice, I’ll take the stairs any time. At work, however, as one of the many quirks of Manhattan, our elevators only stop on certain floors and we’re not able to use the stairs unless it’s an emergency. After a meeting on a floor where the only option was to elevate out, I stepped into a crowded elevator where a conversation was going. “You always capitalize Satan,” someone was saying. The usual questions among non-religion editorial staff ensued. Why is that? What about “devil”? “It’s never capitalized,” came the reply. My profile at work is about the same as it is on the streets of New York. Not many people know who I am or what I do. Although I’ve struggled with this very issue before, on a professional level, I kept silence and waited for my floor.

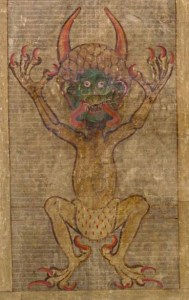

So, was the elevator authority right? “Satan” has become a name, rather along the lines of “Christ.” Both started out as titles. In the Hebrew Bible “satan” is “the satan.” The accuser, or the prosecuting attorney—something like that. As one of the council of gods, the satan’s job was to make sure the guilty were charged of their crimes. Diabolical work, but not evil. By the time of early Christianity, however, Satan had evolved into a name. It is therefore capitalized. It was specifically the name of another title, “the Devil.” Or is it “the devil?” Do we capitalize titles?

In seminary and college the received wisdom among those of my specialization was that there is only one Devil and the title should be capitalized. My elevator colleagues were discussing the number of devils when I stepped out. Traditional theology says there’s only one. Not that the Bible has much to say about the Devil—he’s surprisingly spare in sacred writ. Demons, however, are plentiful. Some people call demons devils, just as many believe that when good people die they become angels. The mythology behind demons seems to be pretty well developed in the biblical world, but again the Bible says little. Demons can be fallen angels or they can be malign spirits who cause illness. Either way they’re on the Devil’s side. But should we capitalize his title? The Oxford English Dictionary doesn’t help, giving examples of both minuscule and uncial. I suppose that’s the thing about the Devil; you never really know where you stand.