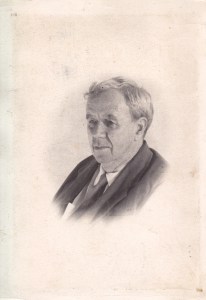

Banned Book Week technically doesn’t start until the week after next, but I have a pathological fear of being late. I don’t know why. It could be that I’m aware time is of limited quantity and much of it is owed to the beneficent corporation that keeps you alive, so you have to trade it for food. And books. Not much of it is left to do what you want to do. In any case, my last book for the 2018 Modern Mrs. Darcy Reading Challenge was in the banned book category. Long ago I had decided it would be Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. I’ve read it before, of course, but it had been long enough that the details had been sanded away and I could only remember parts. One thing I’d forgotten is how much Vonnegut brings religion into the story.

Banned Book Week technically doesn’t start until the week after next, but I have a pathological fear of being late. I don’t know why. It could be that I’m aware time is of limited quantity and much of it is owed to the beneficent corporation that keeps you alive, so you have to trade it for food. And books. Not much of it is left to do what you want to do. In any case, my last book for the 2018 Modern Mrs. Darcy Reading Challenge was in the banned book category. Long ago I had decided it would be Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. I’ve read it before, of course, but it had been long enough that the details had been sanded away and I could only remember parts. One thing I’d forgotten is how much Vonnegut brings religion into the story.

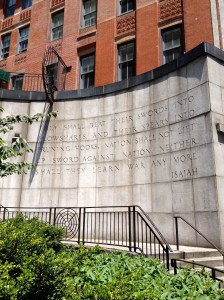

Writers who avoid religion miss the motivating factor of the majority of human beings’ lives. This has always seemed a strange denial to me. I’m not suggesting that every novel should mention religion, but since it is concerned with ultimate interests, it is somewhat surprising that it’s so often overlooked. Not that it plays a major role in Slaughterhouse Five, but any novel concerned with death is inherently in the realm of ultimate concerns, I should think. Right, Dr. Tillich? In any case, I’d forgotten that Slaughterhouse Five was such a poignant, funny, and sad novel. Vonnegut’s experience of World War Two clearly haunted him—most writers are haunted by something—and his musings were, and often are, banned.

If there were banned books in my high school (and I grew up in a conservative area, so surely there were) I didn’t know about them. Let’s face it, teens seldom sit around talking about significant novels. Many, at least among my classmates, didn’t read those that were assigned in English class. Slaughterhouse Five wasn’t one of them. I learned about Kurt Vonnegut from a friend while in college. This is the third of his novels that I’ve read in 2018. The first two I’d never read before. So it goes. I’m keenly aware of time. I’m also aware that those who would ban books are often those who obtain elected office. And when you find that your own nation has turned on you, remembering the fire-bombing of Dresden is an appropriate response. For such reasons Banned Book Week remains important. It should be a national holiday, at least among those of us underground during the firestorm.