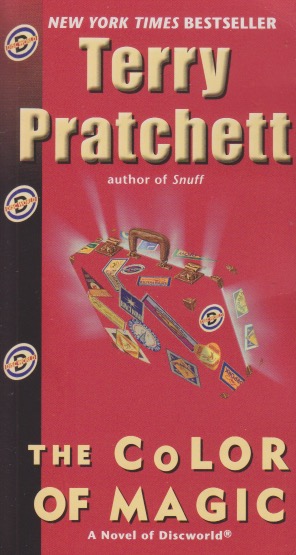

What’s the best kind of April Fools’ Day prank? What about one that occurs nowhere near April first? Actually, I’m no fan of practical jokes. They usually come at the expense of someone and really aren’t that funny. And where does that apostrophe really go anyway? Still, because of a project I’m working on, and because it was available on a streaming service I use, I watched April Fool’s Day in July. An example of holiday horror from the 1980s. Although moderately successful at the box office, the movie never took off to become a cultural icon like, say, Halloween did. In fact, I only recently heard of it. Part of the reason, I suppose, is the ensemble cast is pretty large (nine friends together for a weekend) and none of them played by big names. In case you don’t like pranks, there will be spoilers below.

The trope of a number of young people—often college students—isolated in some inaccessible location is common enough in horror. The optimal number seems to be five, otherwise an hour and a half isn’t really time to get to know everyone’s character well enough. Of course, one by one they get killed off. Since it’s set on April Fools’ Day you’re led to think some kind of serial killer is loose on the island, but in the end the entire thing turns out to have been an elaborate prank. Nobody has really been killed and the audience is on the receiving end of an extended practical joke.

As I try to catch up on horror movies I missed I quite often have to rely on those that come with one of the few streaming services I use. When I was myself a college student I couldn’t afford to go to the movies often. Home video hadn’t really become affordable yet to people of my economic bracket, and besides, I spent a lot of time studying. As the only one in my family that watches horror, finding the time to do so remains a challenge. And there is quite a backlog. I’ve been trying to watch horror set on specific holidays as a way of keeping myself honest. Even that can prove a challenge, however. I can justify the time, however, and the somewhat modest cost, as research. Hey, somebody has to do it. And that’s as good an excuse as any for watching April Fool’s Day in July.