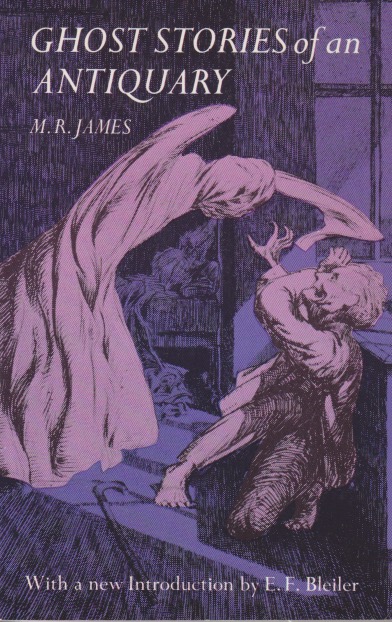

As someone who reads about ghost stories, as well as ghost stories themselves, I’ve long been aware of M. R. James. His Ghost Stories of an Antiquary is regarded as a classic in the ghost-story genre. Sometime in the haze, I recollect it was years ago, I found a copy at a used bookstore on the sale rack. Something I’d been reading about ghost stories lately made me decide to read it through. Now James was an actual antiquary. He was also an academic at Cambridge University. His tales are erudite, generally focusing on some ancient secret that releases ghosts, or sometimes monsters, after the individual who discovers the antiquity. The stories are varied and inventive, but not really scary to the modern reader. They assume a different world. One in which antiquaries were monied individuals—often university men—who have both servants and leisure time, rarities today.

I found myself constantly asking while reading, how could they get so much time off? How did they access such amenities that they could even get to the places where the ghosts were? James’ world is both textual and biblical. It’s assumed the reader knows the western canon as it stood at the turn of the nineteenth century. The Latin, thankfully, is translated. James, it is said, was a reluctant ghost-story writer. A university employed medievalist, he had academic publications to mind as well. Nevertheless he managed to publish five ghost-story collections. Clearly the idea seemed to have had at least some appeal to him.

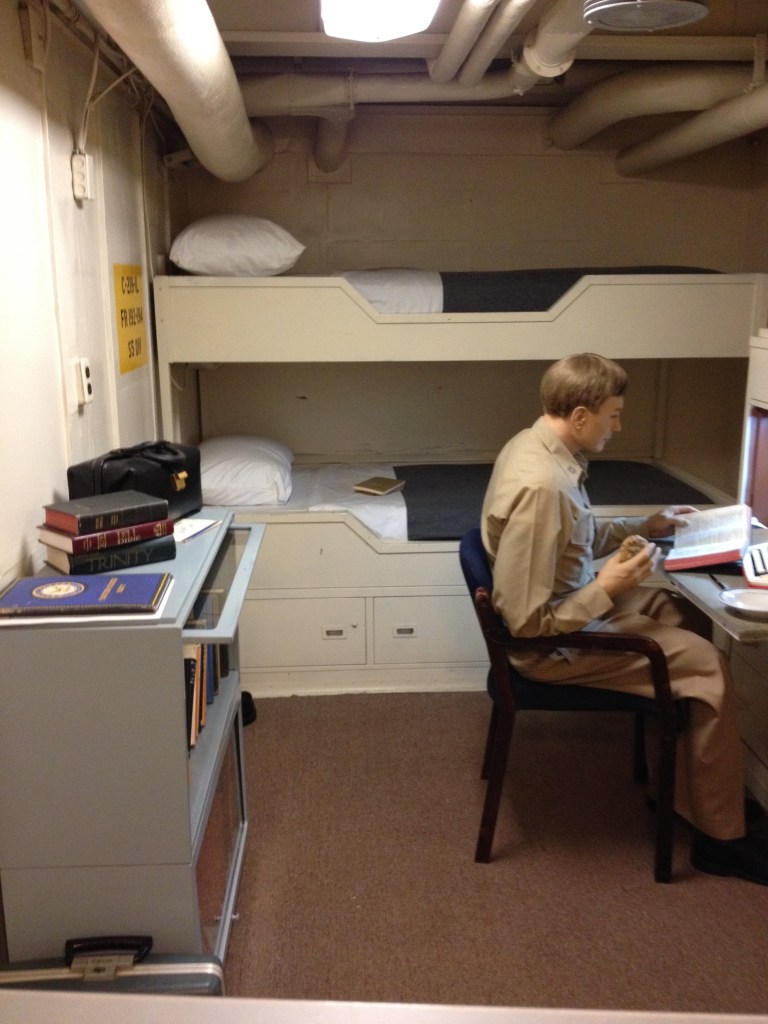

The aspect I find most compelling here is that an academic could admit to such an avocation. While it’s becoming more common these days among the tenured, I always felt like I was walking the eggshell-laden pathway to academic respectability. I was, after all, at a small, haunted seminary that few outside the Anglican communion knew about. It was risky to admit being drawn to anything speculative. Come to think of it, although I read novels while I was there I don’t recall reading many, if any ghost stories. It was scary enough to be about on campus at night, particularly if you were going to the shore of the small lake to try to photograph a comet alone. There were woods punctuated by very little light. On campus ghost stories were fine—the librarian even showed me a photograph of a ghost in the archives—but off-campus such things could never be discussed. I was an antiquary without any ghost stories. James showed the way.