Television has lost its prominence in the internet age. Those of us entering the “senior” category of life’s grades were raised on television. I know I watched far too much as a kid. Now I consider the wasted opportunity to grow minds, and sensibilities, through television. Mostly I blame the sit-com. There’s not much learning going on when someone else contrives scenarios to make you laugh on a weekly schedule. They are beguiling and I watched more than my fair share of them when I was younger. Now, as an adult, I value the more profound examples of early viewing. We didn’t watch The Twilight Zone with the devotion of Gilligan’s Island, but those episodes I did see had a profound effect. The same is true of Dark Shadows. One thing these shows had in common was that they were quite literate, eschewing the mindless competition.

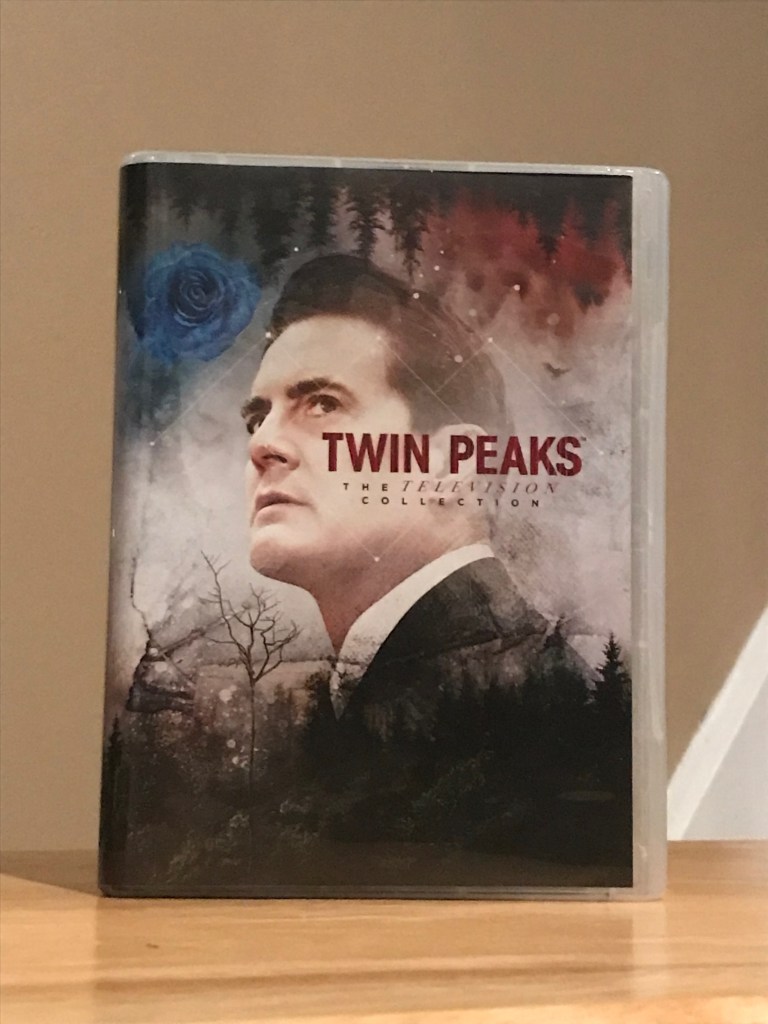

College led to me no longer watching television regularly. That hiatus lasted until my wife and I began watching a couple of weeklies after I’d return from Nashotah House. While at the seminary full-time, television reception was quite poor and we tended toward rented movies on VHS. By the time we moved to New Jersey television had changed so that you needed some kind of magic box to watch even commercial channels. We relied on DVDs of shows we wanted to see. That’s how Lost came into our lives. Now, however, facing senior issues (health, people dying, wondering if retirement might ever happen) I’ve started to revisit television I missed. The X-Files is pretty prominent. Being an historian at heart, I’ve been exploring the inspirations for The X-Files, picking up Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and Twin Peaks. I have to balance this with time for writing since work still claims the lion’s share of my waking hours.

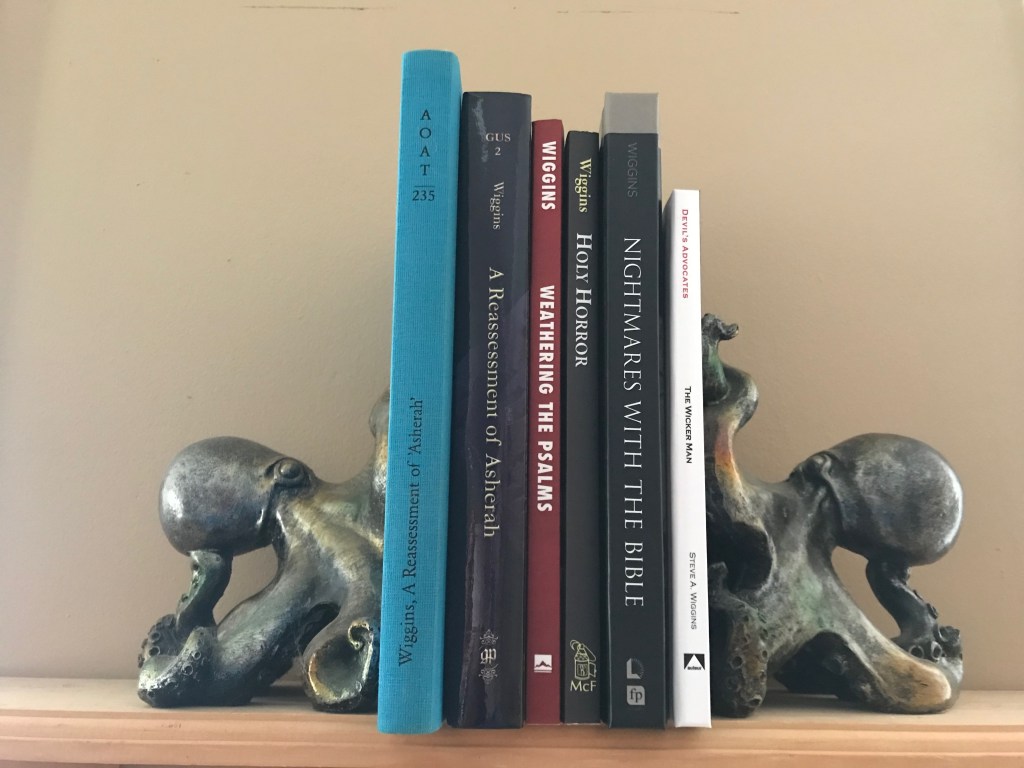

I’ve lost track of what’s on the tube. Now we spend workday evening hours watching intelligent television that we missed back when it aired. We can’t afford it all, of course. Dark Shadows, for example, has over 1200 episodes and “complete sets” are pricey. Lost was either a birthday or Christmas present years ago. I bought The Twilight Zone over a decade ago for a week that I knew I was going to be home alone. We accumulated The X-Files over a number of years. Twin Peaks, since it was only two seasons, wasn’t too expensive. Kolchak is on Amazon Prime. Many of these shows are a kind of therapeutic watching for me. Some might call it escapism, but it runs deeper than that. It becomes part of who we are.