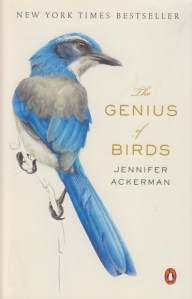

Humans can be quite likable, but we have some nasty traits. One is that we tend to think of ourselves as the only intelligent beings on the planet. The funny thing about evolution is that it gave us both big brains and opposable thumbs—a winning combination to destroy the planet. (Just look at Washington, DC and try to disagree.) Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds is poignant in this context. Page after page of nearly unbelievable displays of intelligence among birds demonstrates that we are hardly alone on the smarts scale. Birds make and use tools, have better memories than most of us do, and can solve problems that I even have trouble following. We tend to take birds for granted because they seem to flit everywhere, but the book ends soberly by noting how global warming is driving many species to extinction.

Humans can be quite likable, but we have some nasty traits. One is that we tend to think of ourselves as the only intelligent beings on the planet. The funny thing about evolution is that it gave us both big brains and opposable thumbs—a winning combination to destroy the planet. (Just look at Washington, DC and try to disagree.) Jennifer Ackerman’s The Genius of Birds is poignant in this context. Page after page of nearly unbelievable displays of intelligence among birds demonstrates that we are hardly alone on the smarts scale. Birds make and use tools, have better memories than most of us do, and can solve problems that I even have trouble following. We tend to take birds for granted because they seem to flit everywhere, but the book ends soberly by noting how global warming is driving many species to extinction.

Homo sapiens (I’ll leave out the questionable and redundant second sapiens) like to think we’ve got it all figured out. We tend to forget that we too evolved for our environment—we adapt well, which has allowed us to change our environment and adapt to it (again, opposable thumbs). Many scientists therefore conclude that we are the most intelligent beings in existence. Ironically they make such assertions when it’s clear that other species can perceive things we can’t. Ackerman’s chapter on migration states what we well know—migrating birds can sense the earth’s magnetic field, something beyond the ability of humans. We lack the correct organ or bulb or lobe to pick up that signal. And yet we think we can rule out other forms of intelligence when we don’t even know all the forms of possible sensory input. We could learn a lot from looking at birds, including a little humility.

The Genius of Birds explores several different kinds of intelligence. What becomes clear is that birds, like people, have minds. Like human beings they come on a scale of intellectual ability that doesn’t suggest only one kind is necessary. For our large brains we can’t seem to get it through our thick skulls that we need biodiversity. We need other species to fill other niches and our own remarkable ability to thrive has only been because we are part of a tremendous, interconnected net encompassing all of life. Other species have contributed to our evolution as we clearly do to theirs. When we end up thinking that we alone are smart and our own prosperity alone matters we are sawing away at the branch on which we sit. Further up the birds look at us and wonder if we really know what we’re doing.