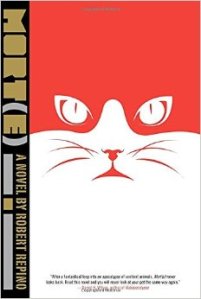

The fear of insects is fairly common among people. It is difficult, however, not to appreciate the “hive mind” and how insects in colonies work for the betterment of all, often at the expense of the individual. Now imagine that the hive mind resents what humans have done to insects over the millennia. And suppose that their massive mind allows them to develop a hormone that transforms animals into partial humans with consciousness and, for the most part, workable hands. Then you’ve got the premise of Mort(e) by Robert Repino. A debut novel about a cat (Mort(e)) and his desire to find a friend in the fog of war that follows the transformation of animals into people, the story is as compelling as it is creative. Add in a strong dose of religious concepts (Mort(e) is considered a messiah among the battered human population, and he has a prophet) and you’ve got a captivating story perfect for comment on this blog.

The fear of insects is fairly common among people. It is difficult, however, not to appreciate the “hive mind” and how insects in colonies work for the betterment of all, often at the expense of the individual. Now imagine that the hive mind resents what humans have done to insects over the millennia. And suppose that their massive mind allows them to develop a hormone that transforms animals into partial humans with consciousness and, for the most part, workable hands. Then you’ve got the premise of Mort(e) by Robert Repino. A debut novel about a cat (Mort(e)) and his desire to find a friend in the fog of war that follows the transformation of animals into people, the story is as compelling as it is creative. Add in a strong dose of religious concepts (Mort(e) is considered a messiah among the battered human population, and he has a prophet) and you’ve got a captivating story perfect for comment on this blog.

While not all novels I read have a religious element, a surprising number do. And this isn’t because I pick stories with religious themes. It is because religion pervades the human outlook on life. Repino’s novel, however, does go beyond a casual mention of religion. It turns out to be central to the plot in a way that, were I to describe it here, would constitute a spoiler, and since I want to encourage reading of Mort(e), I don’t want to reveal too much. Suffice it to say, without religion a large part of the story would be missing. No matter whether you believe religion is good or bad, you’ll find plenty to think about here.

These days I read novels liberally mixed in with non-fiction reading. Sometimes I’m disappointed after I spent a few hours on a book and find it to lack substance. (Sure, I do read as a guilty pleasure from time to time, but here I mean the kinds of books you invest in.) Mort(e) is a substantial story. The world in which the protagonist operates can be described as apocalyptic, and end-of-the-world scenarios have a way of raising questions about what we believe. The time spent reading Mort(e) is a good return on investment. And once it has been out there long enough, I’ll want to return to that plot spoiler to investigate it further. It’s that kind of book.