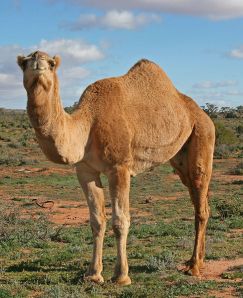

Abraham, as the progenitor of the three major monotheistic religions, bears a tremendous weight on his weary shoulders. It is the weight of history. Or lack thereof. I may be a few years outdated here, but the earliest figure historically attested in the Bible is (or was) Omri, the king of Israel who spawned the notorious Ahab. Prior to that, historical records are pretty silent. Yes, I know the Tel Dan stele mentions “house of David,” but that is like mentioning Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory—it doesn’t make Mr. Wonka any more real (even though you can buy a Wonka bar at some candy stores). That means that, in the jumble of biblical history, everyone in Genesis falls into the questionable historical category. Even if Moses (himself historically dubious), wrote Genesis (and he didn’t), he wouldn’t have known Mr. Abraham personally. He had been long dead. If he’d ever been born. I’m getting worried about his camels.

Religions have often tied themselves to historical claims. Such claims are always tenuous and negotiable. For instance, I watched a movie about Abraham—Lincoln, it was called—where I learned quite a bit that I didn’t know about a very historical Abraham. At the same time, I knew the movie wasn’t history. When we rely on history to cite our superiority (often one of the functions of religion), we had better be willing to take the risks. The first biblical historical figure is a “bad guy” king of a secessionist kingdom, this time in the north. Even once we learn that the storied characters of the Bible may have never trod the earth, we don’t leave them as camel fodder. They are part of the tradition, whether they participated in history or not. I realize, however, for some it would be easier to swallow a camel than to strain out this particular gnat.