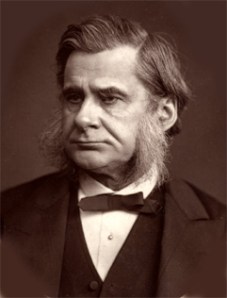

An opinion piece in Saturday’s New Jersey Star-Ledger highlights the 150th anniversary of T. H. Huxley’s Man’s Place in Nature this month. Well, Huxley may be forgiven for writing in the idiom of his day—he was Darwin’s contemporary after all—when he really meant humanity’s place in nature. The article, by Brian Regal, points out the common fallacy that evolution, as propounded by Darwin, says that we descended from monkeys. Quite apart from the insult to monkeys, Huxley was the one, as Regal notes, who made explicit something about which On the Origin of Species kept decidedly mum: the evolution of humans. People did not descend from monkeys. Nobody except religious opponents ever suggested that they (we) did. Evolution is a biological fact, and monkeys are evolved just as we are evolved. We had a common ancestor somewhere back a few millions of years ago.

This neverending story of religion (of some sorts) fighting evolution should capture the fascination of anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists. It shouldn’t be ignored. Darwin wasn’t trying to start any fights. Huxley, well, he may have been, but with good cause. The facts, even in the 1850s, were definitely pointing to descent with modification. In fact, breeders of dogs and pigeons and other animals had known this for centuries. All that Darwin and Huxley attempted was to be intellectually honest with the evidence. It was religious believers who, reading between the lines, picked this fight. The Bible, after all, seemed to say we’d been created on day six (or day one, if you read Genesis 2 literally), and that meant science had to be wrong. Religion is used to setting its own terms. The debate is in the cathedral, not in the academy. Although by the end of the nineteenth century nearly all major branches of the church had come to some kind of understanding of the facts, the issue flared up with again around the time of the First World War with the advent of “social Darwinism.” Then, the religious objectors claimed, we did not descend from monkeys.

Funny thing is, Darwin and Huxley would’ve agreed. Instead, insidious motivation was attributed to some of the greatest minds in science. Accusations were made that everything in the lives of both Darwin and Huxley gainsaid. Natural selection made Darwin ill with its implications, but he could not shy away from the evidence. He believed in truth. Although Huxley coined the term “agnostic” to define his position, he had good reason. The biographies of these scientists are well worth reading before making accusations. So as we stand (or more likely, sit) on the sesquicentennial of Man’s Place in Nature, it might be a good opportunity to assess whence the friction is arising. We claim, in our still limited understanding, that monkeys can’t speak. (I’ve seen the movies and I know differently, nevertheless…) If they could, I imagine the debate would go something like this: “those hairless creatures who say that we are less important than they, they have the audacity to claim a common ancestor with us? Maybe evolution is a myth after all.”