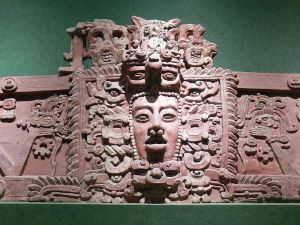

At a hotel during a recent excursion, I saw a National Geographic (I think) special on Gobekli Tepe (this is the fate of those of us kept from a daily sustenance of academic listservs bearing the most exciting news). Gobekli Tepe is an archaeological site in Turkey, discovered several years ago by Klaus Schmidt of the German Archaeological Institute. It is an odd site, dating back to some 11,000 years ago, that consists of megalithic (big stone) constructions earlier than Stonehenge or the great pyramids of Egypt, both dating from the Bronze Age, roughly. The complex of odd buildings seems to be religious in function because they bear no practical purpose, and the implications of the site are that our earliest steps towards civilization have been misinterpreted from the beginning. We have been taught that domestication of plants and farm animals led to fixed centers of living. Gobekli Tepe suggests that religion led to settled life and farming came later.

The implications of this are rather startling for those of us who’d been working on the assumption that religion developed as a way of keeping the gods happy after people had the luxury of surplus food brought on by agriculture. It turns out that hunter-gatherers learned to live in settled locations because of religion. That is, religion, instead of being just another component of culture, is what led to culture in the first place. In a climate where the most vocal intellectuals insist that religion must be shut down, chopped off at the roots, and burned in the oven of rationality, we see that none of us would be enjoying our urban lifestyles if religion hadn’t brought us together in the first place.

There is no doubt that religion may be taken to extremes, and that when it is, it becomes dangerous. Religion, however, is no foe to rational thinking. Gobekli Tepe is a site of astounding engineering for Stone-Age hunter-gatherers. Engineering is applied science, and so these people were using their understanding of the world to establish a ritual site for the practice of their religion. They needed to live nearby, although they still had to spend their days chasing animals and gathering foodstuffs along the way. Religion made them realize that life together was a necessity for humanity to thrive. We should take a more balanced view before declaring religion a source of evil only. We may never be able to coax the gods into the laboratory, but that doesn’t mean that they don’t have a very important function for human civilization. If they are taken in reasonable doses, they might even lead to astounding transformations.