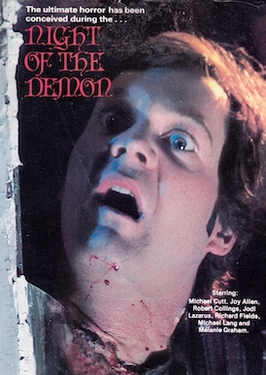

There’s a connoisseurship about it. Making bad films, that is. It’s a wonder that Night of the Demon—I should specify 1980 as the year—hasn’t really become a cult film of any standing. You can tell the maker tried hard to shoot a reasonable film, but with a nearly Ed Woodsian level of incompetence. It lacks Woods’ artistry, however. For those just getting on the Bigfoot kick in the new millennium, it might help to know that Sasquatch was big in the seventies. Yes, the first real efforts to sort this thing out came about when the psychedelic seventies were underway. The documentary The Mysterious Monsters came out in 1976. The first serious efforts to explain Bigfoot as not just a hoax began. And James C. Wasson, Jim L. Ball, and Mike Williams took a shot at making a horror film of the hairy guy.

The acting is about the worst you’d care to see, and the script is abysmal. The effects are anything but special, and the flashback scenes incongruous. But it does have significance for religion and horror. It goes like this: a professor and some students go to investigate a series of Sasquatch-related murders. They’re led to “Crazy Wanda,” who lives alone in a remote cabin. Wanda, when finally persuaded to talk, reveals that her crazed preacher of a father killed her Bigfoot-hybrid baby. His followers still perform demonic rituals in the woods, worshipping the Sasquatch. Wanda had burned her father to death in retaliation for killing her child—she kinda likes Bigfoot, it turns out. The professor and students, naturally, fall victim to the beast.

Only the professor survives. He’s assumed to be criminally insane and suspected of murdering his own students. It’s almost painful to watch a movie where everyone is trying so hard to do it well, but just can’t seem to manage it. The plot line about the cultists is immediately dropped after an intended rape ritual is interrupted by the professor. Wanda’s preacher father, who seems to fit into no particular form of Christianity, has no motivation beyond avoiding Hell for himself. At one point he seemingly admits killing her mother. There’s even a scene where Bigfoot kills two Girl Scouts. With all of this going for it, you might think it would’ve picked up a following. It has some fans, I’m sure, but I’m not certain that it’s well enough known to make it onto lists of worst movies of all time. More’s the pity since it would absolutely deserve it.