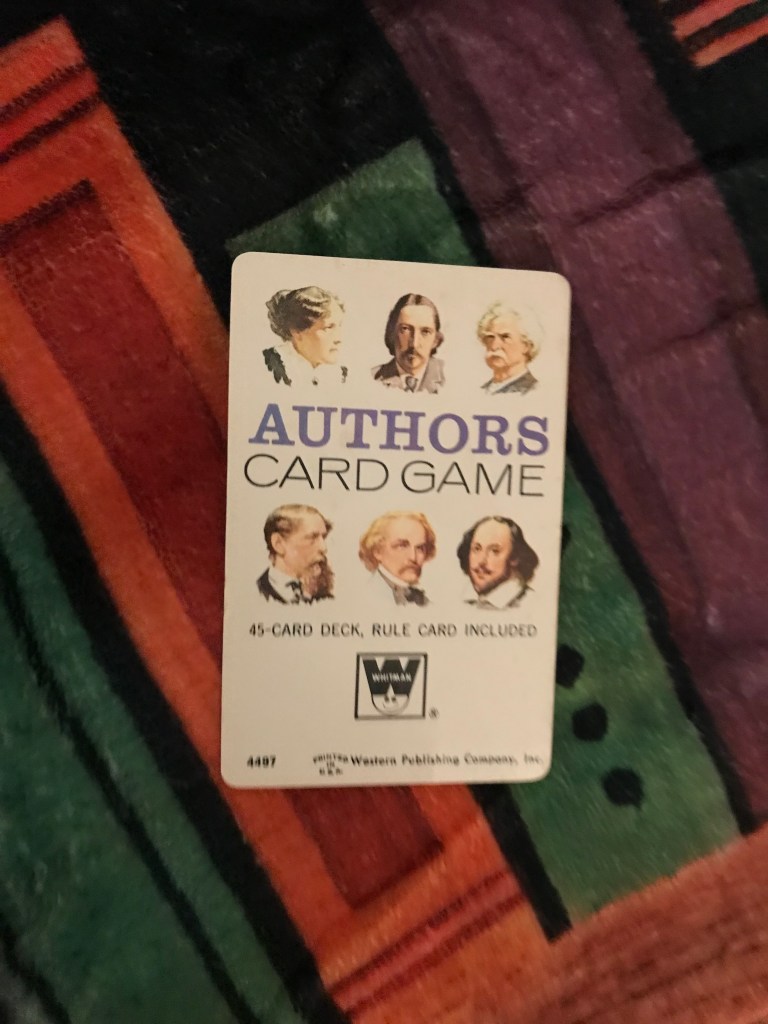

It happened in Salem. In 1861. The classic American card game, Authors, was published. G. M. Whipple and A. A. Smith devised the game, which has remained available ever since then. It’s one of the few games I remember having as a kid. We, of course, had the Bible Authors game as well, which I’m kind of nostalgic for, but not enough to see if it’s on eBay. The object of Authors, an early form of “Go Fish,” is to collect sets of four cards for each author. Each card lists a different work. Poets are represented by poems, of course, but prose authors mostly by books. I have to confess to having eBayed this some time back and having beetlebrowed my family into playing it with me. I noticed, however, a few curious omissions.

Edgar Allan Poe isn’t among their number. Neither is Herman Melville. Rather strangely, they included Shakespeare—centuries earlier than the others—and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. The only female is Louisa May Alcott when there were perfectly acceptable Brontës in the room, as well as Jane Austin. The game reflects its time. A couple years back I was in Michaels—you know, the arts and crafts supplies store. In fact, Michaels is one of those places for family outings, for families like mine. (We tend to be creative types.) While I’ve never been into scrapbooking, I walked down that aisle and found a set of stickers labeled “Literature.” Two authors were represented: Shakespeare and Poe. People smarter than me have argued that worldwide Poe is probably the best recognized American author. I think it’s safe to say Shakespeare occupies a similar role in Britain.

Poe had fallen afoul of many in America because of an intentionally damning obituary by Rufus Wilmot Griswold, whom Poe had named his literary executor. If it weren’t for Poe nobody would likely know Griswold’s name today. In 1861, when Whipple and Smith were inventing their game, Poe wasn’t really considered worthy of emulation, largely because of Griswold. He wasn’t the kind of guy you’d want your kids to be too curious about as you tried to teach them about literature. Authors has gone through over 300 editions over the years. I’ve never seen any of them (apart from Bible Authors) other than the Whitman edition from my childhood. Each time I pick it up, smell the cards (go ahead—try smelling your Kindle), and thumb through the authors I feel like I’m missing something. Go fish.