I keep track of my reading on both this blog and Goodreads. It’s a little easier to follow the numbers on Goodreads, so I tend to use their stats. One thing I’ve noticed in tracking my pacing this year is that academic books slow me down. I desperately hope this isn’t endumbification, but I feel the need to consult the experts even as I try to write for a wider audience. Having been trained as a professional researcher, it’s difficult to let go and just read the popular books—those with the style I need to learn to emulate. But academic books take so long to get through. Maybe it’s because they’re consciously designed not to be fast reading. They take time and have concepts that require thought as your eyes consume the words. They’re also the language I spoke for a good few decades.

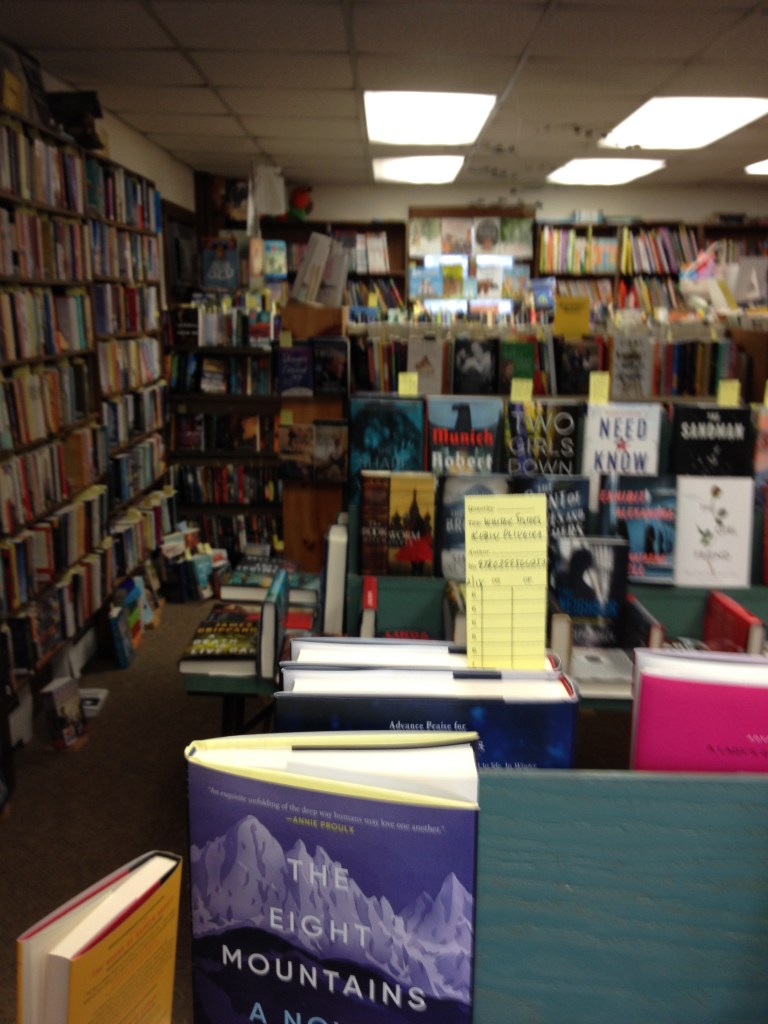

My nonfiction reading pile constantly grows taller and I can’t seem to keep up. Largely it’s because many of them are academic books. I’m aware that in the real world, where books sell more than a couple hundred copies, that those who can’t claim “Ph.D.” after their names make the most successful writers. A few of my colleagues have broken through to mainstream publishing, but they generally have university jobs, and tenure. They don’t have a 9-2-5 schedule that holds their feet to the fire for the lion’s share of every day. There are writers, I’m learning, who hold down jobs and write more successful books. They generally aren’t academics, however. Normal people with intense interests that they express beautifully in words. Then they go to work.

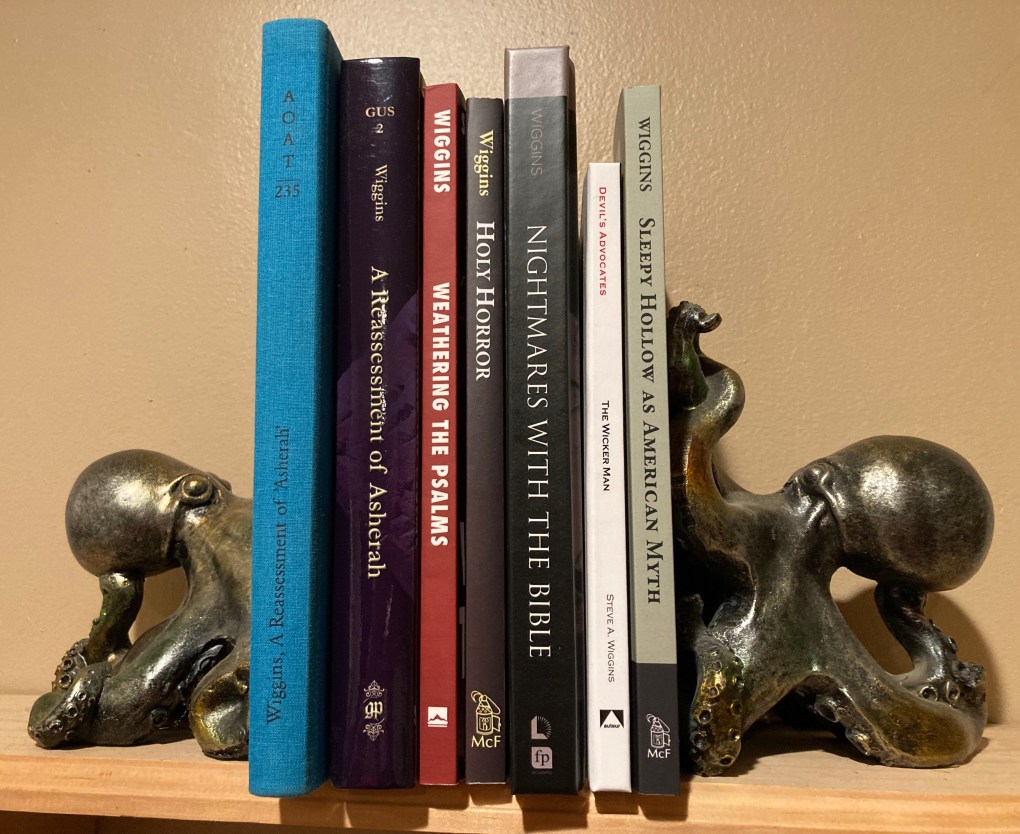

I’m trying to break into that world. I know that the publishers I’ve resorted to have been academic publishers. They don’t really compete with the trade world, nor do they really even try. Their’s is a business model adjusted for scale. When you can’t sell in volume, you need to jack up the price. But to have something intelligent to say about a subject, you have to read books. I guess I need to learn to read non-academic non-fiction. Kind of like I have to drink decaf when I have coffee (rarely) and have them add oat milk to make it a latte. This is difficult for an old ex-academic like me. I want to know how writers know what they do. What are their sources and how deeply did they dig? As I set my shovel aside I realize that I’ve begun to dig that academic hole yet again.