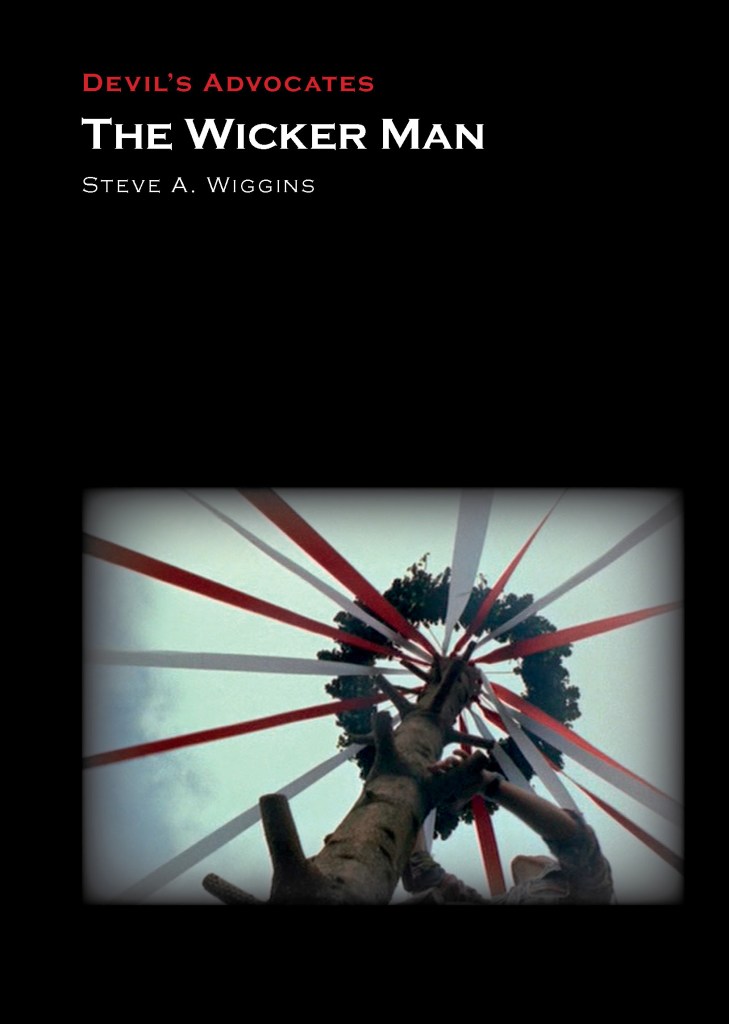

Would you rather never write a book or write a book that’s easily forgotten? This question springs from a recent exercise of trying (unsuccessfully) to count the books I’ve read. I mean going through and putting a finger on each one and counting, if I’d read it. I encountered a surprising number of ordinals that evoked a blank stare—I don’t remember the book at all. Or I remember having read it, but don’t recall what it was about. (In one instance, the book was one my wife read, and not me. That explained a lot!) This got me thinking about what it takes to write a memorable book. I’ve always been one to prefer either speculative fiction or the classics. (I’m aware that “classics” are now being dismantled because they don’t represent all groups. I’d call them “white men’s classics,” but a surprising number of them were written by women.) If a book has a speculative element strong enough I will recall having read it. I like weird stuff.

I’ve read books where parts of them, at least, have stayed with me for half-a-century. I remember specific things I read as a child (and no, I’m not talking about Barney Beagle—although I do remember that too). I like to believe that even the bits that are hazy indicate that the book isn’t truly lost, but buried somewhere. The human mind has an amazing capacity to absorb things. I’ve read at least three thousand books in my life—I have no idea how many, actually, but Goodreads has me at 1,000 and I started using it in 2013. I’d been intentionally reading for about forty years already, at that point. Three of them while working on my doctorate.

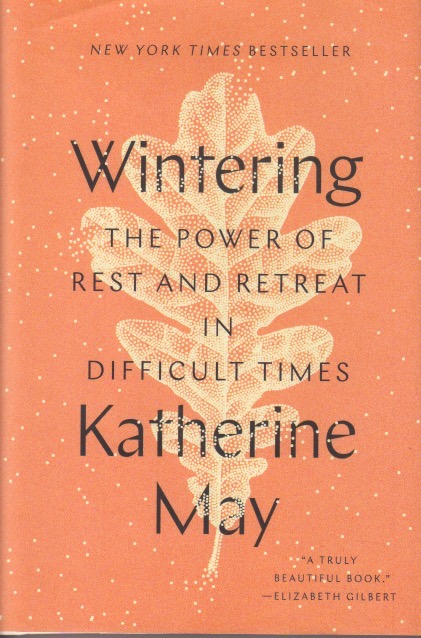

I recently (within easy memory) read a Doc Savage novel. I’d read the entire series, or pretty near, as a junior high schooler. Anyway, there were well over a hundred of them. I remembered nothing in my recent re-read beyond Doc’s band of five companions. The story was completely unfamiliar to me. One of the more recent books I know I read but couldn’t remember the story at all was a New York Times bestseller. I guess if I’ve forgotten the author he’ll still be okay on Mars in the future since many others must remember something about it. I’ll be long gone by then, both on Mars and down here, I’m sure. I do hope even by then something will remain of all the books I’ve read.