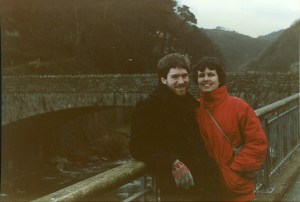

The Edinburgh Festival draws people from around the world to experience culture and fun in one of Europe’s most beautiful cities. The festival also attracts the fringe—artists not associated directly with the festival, but who get included in what used to be a huge, thick catalogue that would keep us busy for hours, considering what a student and spouse could afford, and what you could not afford to miss. One year a group called Outback was performing at an area church. It featured Graham Wiggins on the didgeridoo—an Oceanic aboriginal instrument that is essentially a tree branch hollowed out by termites. It’s so long ago now that I can’t recall if I knew ahead of time, but the leader of the group, the didgeridooist, was Graham Wiggins. While not exactly a rare surname, Wiggins isn’t common either and when I saw him a strong family resemblance was immediately obvious. So much so that after the concert we went to meet him only to find out his Wiggins side was from Oxfordshire. Mine was from South Carolina.

Graham Wiggins, who was a month younger than me, was known as “Dr. Didg” because he held a D.Phil. in solid-state physics from Oxford University. While an American, he had decided to stay in the UK to make a living from his music. Some months later, on a Christmas break, we saw him busking in Bath on a chilly night. We bought the band’s second CD from him that evening. When my wife put on our Baka disc the other day, I grew curious whatever became of him. I was surprised and saddened to learn that Graham Wiggins had died three years ago. I knew we shared a surname and a family resemblance, as well as UK doctorates, but I learned he went to the British Isles from Boston University, which is where I had studied before attending Edinburgh. He left the year I arrived.

Websites are reluctant to say of what Wiggins died. I learned of this just days after finding out that a high school classmate had passed away, so mortality has been on my mind. Wiggins, unlike this Wiggins, was a talented musician with a brilliant mind. We saw him interviewed on television about the physics of didgeridoo playing. I never did find out if we were distantly related. The US Wiggins clan from South Carolina doesn’t have strong genealogical interests, although we know they started out in North Carolina many years ago. It stands to reason they had come from England at some point, since it’s an English surname. I only met Graham of the clan twice, but now I can’t get the fading didgeridoo sounds from my mind.