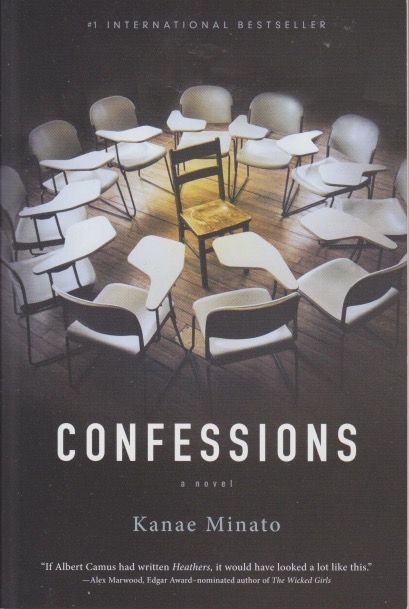

I’ve read that horror and dark academia go together. You might almost say like peanut butter and chocolate. One example of this is Confessions, a novel by Kanae Minato. There are no monsters in it, but two people driven by revenge. The difficulty with such a book would be to describe it without giving too much away. So I’ll start by placing it in the category of dark academia. It is a middle-school story with a distinct darkness and dread to it. As a kind of epistolary novel, it’s told in several voices, beginning with a teacher in Japan and her final lecture to her students. The lecture is final because her four-year-old daughter had died on the school grounds. More than that, she was murdered by a couple of the students. The novel explores the motivations and actions of the students involved, and sometimes their parents. The school setting makes it dark academia.

The horror part comes through the slow building of the ruined lives that follow in the wake of the murder. Believing that one form of revenge is at play, the reader finds subtle shifts as characters become monstrous. One is clearly a sociopath. Another is becoming one. The idea of people harming one another because of their grievances is real enough. We are emotional beings and sometimes our pain for those we love reaches a point of striking out. Most of us learn to refrain, accepting that suffering comes into every life. A minority insist on bringing others into their personal hell. This novel explores people like that. This makes it a horror story.

Originally written in Japanese, it has a kind of gentleness to it. A decorum. Underneath, however, trouble is brewing. It accumulates over the novel as additional perspectives join the narrative of what happened. Stories like this take a bit of rethinking for those of us who like to believe our narrators. Most events have more than one outlook and Confessions ably guides us through several, reaching a conclusion that is both satisfying and chilling. This is one of those novels that underscores what a fraught time middle school is. Powerful emotions are at play and even though they may be sublimated for adults in society, they still exist. We learn when we can and can’t act upon them, and how we may do so. That’s a large part of education, beyond simply learning from books. As reading becomes more and more electronic, I do wonder if we’re ushering in a new darkness that hasn’t been fully considered.