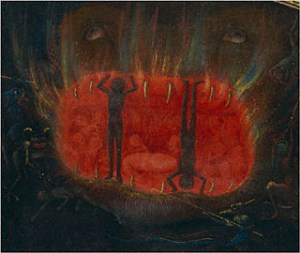

Chaos is a monster. More than personal opinion, that’s a biblical view. If, like many modern people with theological training, you’ve been taught that Genesis narrates a creation out of nothing, you’ve become a victim of this monster. You see, although ancient Israel had no “systematic theology”—the Bible can be quite inconsistent if you’re willing to read what it says—the view that chaos was constantly lurking outside the ordered realm of creation was a common one. One of the more intriguing episodes in Ugaritic mythology involves a broken text where the god Hadad, aka Baal, refuses to allow a window in his palace. The reason? Apparently he feared chaos (in the form of Yam, the sea) might slip in and kidnap his daughters.

More than a theological statement, the story of creation was actually a singular episode in Yahweh’s ongoing struggle against chaos. Step outside and look at the sky. If it’s blue it’s because there’s unruly water being held back by a great dome over our heads. If it’s gray, it may be raining, or it probably will be soon. Stroll to where the land ends. What do you see? Water. That water is lapping at land, trying to take it over. Although the ancients didn’t have geologic ages (the Mesopotamians came close, with ancient kings living thousands of years) rivers eroded land and they had tendencies to flood. The thing about chaos is that it makes you start again, from the beginning.

One of the many unfortunate things about biblical literalism is that it loses sight of this biblical truth. It exchanges something everyone can understand for a theological abstraction that makes no sense in the world that we experience. Ancient belief held that the human role in the world was to fight chaos, not to get to Heaven. In fact, in the Hebrew Bible there’s no concept of Heaven at all. Instead, the commandments were all about order. You can’t build on the water. What you do build water tries to wash away—Israel has a rainy season, and one of the characteristics of such seasons is the occasional violent storm and heavy rains. Although we need the water from the heavens, heavy rains cause, well, chaos. In ancient thought, this was the monster hiding in plain sight. That blue sky is a reminder that a dragon awaits. Rather than starry-eyed Heaven-gazers, the ancient biblical person was a monster-fighter. And that’s the biblical truth.