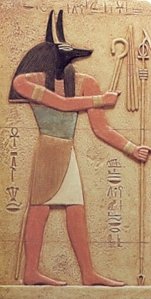

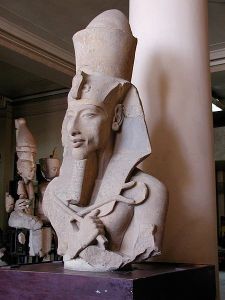

With the moon and Jupiter waltzing slowly so high in the sky, radiating such brilliance early in the morning over this past week, it is understandable how ancient people came to see the gods as material objects. The course of progression seems to have been physical gods to spiritual gods: the earliest deities ate, drank, made love, fought. They were of the same substance as humans, or at least of the same psychological makeup. The Egyptians, Zoroastrians, and Greeks all toyed with ideas of beings of “spirit”—non-corporeal entities that did not participate in our material world, but were able to influence it. In the world but not of it. The tremendous gulf between great goddess and material girl was born. Today that concept is taken for granted, especially in western religions. We are locked into physicality while God is free to come and go.

Many religions respond to this by suggesting that we should look beyond the physical to the majesty hidden from biological eyes. And yet, physical creatures that we are, we are drawn back to material means to demonstrate our spirituality. One of the perks of working for a publisher is the constant exposure to new ideas. At Routledge I have been learning about the rising interest in material religion: the manifestation of religion through physical objects and rituals. This aspect of religious life easily devolves into a cheapening of faith into mass-produced, religious knickknacks and kitsch. Some mistake this for the real thing. While living in Wisconsin, my family used to visit the spectacular Holy Hill, the site of a Carmelite monastery atop a large glacial moraine. On a clear day you can see Milwaukee from the church tower. It is a large tourist draw.

No visit to such a shrine would be complete without the obligatory stop at the gift shop. Even the non-believer feels compelled to buy some incredibly tasteless artifact to keep them grounded in reality. Many of the items—giant glow-in-the-dark rosaries, maudlin mini-portraits of the blessed virgin Mary (BVM as the insiders call her, not to be confused with BVD) and the crucified Lord on all manner of crosses, line the walls and shelves. This commercialization is not limited to the Catholic tradition. Evangelical groups realize the importance of branding as well, passing out cheap merchandise (or better, selling it) with Bible verses emblazoned on it. These signs of faith sell themselves, but they blur the sacred distinction between human and divine. Does religion point to a reality behind the physical? This is its claim, but what is the harm in making a bit of cash on the side, just in case?