It is not exactly pride that I feel when I see my undergraduate college featured in a Chronicle article entitled “Group Aims to Help Conservative Parents Counter ‘PC Indoctrination’ at Colleges.” I almost feared to scroll down the page. Yes, good old Grove City College has to thrust its manly credentials into the face of reason once again. The problem is that what such conservative groups decry as “indoctrination” is, in reality, critical thinking. It took me a long time to learn this distinction. I grew up in a conservative family, but I didn’t choose Grove City because of its flaming commitment to sixteenth-century values. I chose Grove City because it was a selective, intellectually honest school close to home. Being a first generation college student, I had no family tradition on which to draw. Guidance counselors didn’t know what to do with a religious kid who seemed to have some smarts. Other colleges seemed so far away. I didn’t even know what I wanted to study. You see, being raised in humble circumstances you learn to react to the many unpleasantries that life throws at you and there really isn’t time to plan out a future. It never works out that way in any case. I felt driven, but I didn’t know where I was going. Some day I hope to find out.

In the meanwhile, Grove City College has grown even more reactionary than when I was there in the 1980s. The Chronicle article states that “Conservatives have long complained about a perceived liberal bias in higher education,” and that Jim Van Eerden, an “entrepreneur in residence,” (shudder!) at Grove City has started the ironically named “FreeThinkU” to counter the liberalities students receive in school. Talk about your mixed messages! I wonder if Van Eerden has ever considered that Free Thinking has a long association with the very progress he abhors. Free thinkers gave us the gifts of evolution, rational thought, and for a while anyway, free love. Free thought gave us Kate Chopin, J. D. Salinger, and Margaret Atwood. They literally gave us the moon and have landed our probes on Mars. Somewhere lost in space a metal plaque is spinning in infinity with a naked couple and directions to planet Earth. I think the mis-named FreeThinkU might be better rechristened as Don’tUThink.

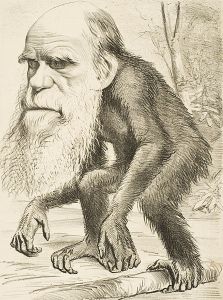

Higher education has a long, long history with religious thinking. Early universities were often outgrowths of theological colleges. Over the centuries, as our thinking matured, the ways of the past were recognized for what they were—outdated, short-sighted, unchanging for the sake of being unchanging. The reality that meets our eyes through the lenses of logic sometimes claims beehive hairdos and horn-rimmed glasses and greased back business haircuts as its victims. The earth is warming up. We did share a common ancestor with the apes. Our universe is even larger than we ever thought. And yet “FreeThinkU” suggests that we need to set the clock back a little. Maybe just a couple of centuries, but enough to hold our kids in the twilight of misperception. Progress has to be more than raping the earth and getting rich. Free thinking has to be a willingness to use the minds we have. I wonder what the aliens will say when they land here, our Pioneer 10 plaque in hand. If they land in Grove City, I suspect, they might feel they were sold a false bill of goods.